Astronomers have detected something strange in two disc galaxies located just beyond the Milky Way - a double-layered arrangement of stars shaped just like a peanut shell, nested one inside the other, bulging rather visibly at their centres.

Galaxies NGC 128 and NGC 2549, which are roughly 200 and 60 million light-years away from Earth, both appear to harbour this rare three-dimensional structure within their stars - something that no one's ever seen before in more than one layer.

Oh and did I mention that these structures are massive - as in, almost galaxy-sized?

"Ionically, these peanut-shaped structures are far from peanut-sized," says one of the researchers, Alister Graham from Swinburne University of Technology. "They consist of billions of stars, typically spanning up to a quarter of the length of the galaxies."

Graham and his team were able to detect these structures using newly designed software that can interpret data collected by the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope and the Sloan Digital Sky Survey in unique ways.

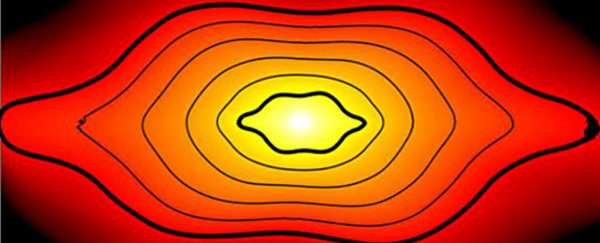

While astronomers have known about galaxies having single peanut shell structures for many years - the Milky Way has one - it was only when they were able to analyse a galaxy like they do in the image above, that they could see the 'inner peanut shell'.

The large peanut shell-shaped bulge at the centre of the disc galaxy NGC 128. Credit: B Ciambur

The large peanut shell-shaped bulge at the centre of the disc galaxy NGC 128. Credit: B Ciambur

That inner structure is about five times smaller than the structure it sits inside, and now that we know it exists elsewhere in the Universe, it's time to figure out if there's one lurking in our own galaxy.

Astronomers are also hoping to use these inner structures to extract certain clues about a galaxy's very early history, and maybe even hints about the future.

"This is the first time such a phenomenon has been observed," said study leader, Bogdan Ciambur, who developed the software. "We expect the galaxies' surprising anatomy will provide us with a unique view into their pasts. Deciphering their history can tell us about transformations that galaxies like our own Milky Way might experience."

So how did these twin peanut shell layers actually form?

As with many of the mysteries of outer space, there's still a lot to learn, but astronomers suspect that the bulges you can see in the images above are linked to the way that many stars across the centre of thin, rotating galaxy discs tend to align in a kind of 'bar-shaped' distribution.

Both NGC 128 and NGC 2549 are known to have two of these stellar bars.

These bars are likely bent above and below by a galaxy's central disc of stars, the team suggests in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, which gives rise to the bulges of the peanut shell.

"The instability mechanism may be similar to water running through a garden hose," says Ciambur. "When the water pressure is low, the hose remains still - the stars stay on their usual orbits. But when the pressure is high, the hose starts to bend - stellar orbits bend outside of the disc."

There's obviously a whole lot more work to be done to figure out exactly why and how these things get made, but the Swinburne team is confident that, now we know that double layer exists, they can test the growth of stellar bars over time, including their lengths, rotation speeds, and periods of instability.

Dear Universe, please never stop being weird. Thank you.

Swinburne University of Technology is a sponsor of ScienceAlert. Find out more about their innovative research.

The peanut shell-shaped bulges of galaxy NGC 128 (left) and NGC 2549 (right). Credit: SDSS, B.Ciambur.

The peanut shell-shaped bulges of galaxy NGC 128 (left) and NGC 2549 (right). Credit: SDSS, B.Ciambur.