If there were awards for most powerful and persistent active volcano in the Solar System, first place would go to the awesomely named Loki Patera on Jupiter's moon, Io.

Two years ago, researchers took advantage of a rare astronomical event to create a detailed map of this king of volcanos, finding a wave of fresh magma bleeding up onto the moon's surface.

The team of astronomers led by University of California, Berkeley, have only recently published their measurements of the geological phenomenon, based on a sequence of heat map images taken through the Large Binocular Telescope in Arizona in March 2015.

Before we go on, just let that sink in – the measurements weren't taken by some probe or satellite, but by a telescope on a mountain several hundred million kilometres away.

This was helped by the ice-moon Europa passing in front of Io, which thanks to its coating of frozen water doesn't reflect infrared wavelengths, providing something of a shadow to allow the pattern of temperatures on Io's surface to stand out.

"There was so much infrared light available that we could slice the observations into one-eighth-second intervals during which the edge of Europa advanced only a few kilometres across Io's surface," said researcher and developer of the infrared camera technology, Michael Skrutskie of the University of Virginia.

While these kinds of eclipses have been used to study Io before from far away Earth's surface, advanced optics technology have only now allowed scientists to map hotspots down to a resolution of about 10 kilometres (6.2 miles).

Several decades of previous studies described an active volcano surrounded by a depression, or 'patera', about 200 kilometres (124 miles) across, filled with cooling rock that was resurfaced every 400 to 600 days with waves of lava that flowed around the basin at a speed of about 1-2 km (about a mile) per day.

This raised an interesting question: just where did this fresh lava come from?

One possibility was the lava was the result of regular eruptions spewing out of Loki Patera itself. The second possibility was through something called overturning.

As molten rock cools on the surface it increases in density, until the chilled crust collapses into the still molten rock beneath. Each collapse can make the next section unstable, creating a creeping wave of magma across the field to cool in its place.

It turns out this is precisely what is happening around the Solar System's most badass volcano.

"If Loki Patera is a sea of lava, it encompasses an area more than a million times that of a typical lava lake on Earth," said lead researcher Katherine de Kleer, a graduate student from University of California, Berkeley.

"In this scenario, portions of cool crust sink, exposing the incandescent magma underneath and causing a brightening in the infrared."

The differences in temperature revealed how recently magma had been exposed, telling a story about a wave of magma starting from the northwest corner of the surrounding basin, gradually moving clockwise, and a more recent wave starting further east.

"There must be differences in the magma supply to the two halves of the patera, and whatever is triggering the start of overturn manages to trigger both halves at nearly the same time, but not exactly," said de Kleer.

"These results give us a glimpse into the complex plumbing system under Loki Patera."

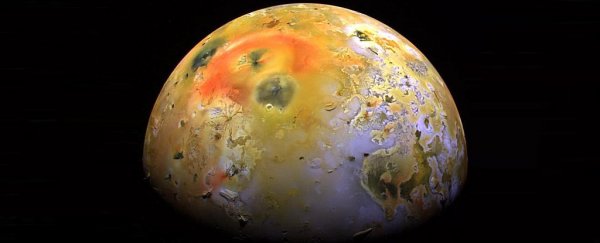

The image below gives you some idea of the patera and the volcano, with the waves of magma taking between 180 and 230 days to roll around its perimeter:

Katherine de Kleer, UC Berkeley

Katherine de Kleer, UC Berkeley

While more observations will provide more detail about Loki Patera's "plumbing", the team will have to wait until 2021 until Europa aligns with Io again.

Lava has been spilling and cooling around the volcano before Viking first took some snaps back in 1979, so it's unlikely to be falling quiet any time soon.

The entire moon is massaged constantly by Jupiter's tidal forces, creating hundreds of volcanos all over its surface that channel molten rock and sulphur and send occasional plumes of dust and sulphur-dioxide gas high into its thin atmosphere.

Io might not win any awards for being the prettiest place in the Solar System, or the most suitable for a holiday destination, but it sure makes up for it in excitement.

This research was published in Nature.