Australia's dinosaur record is one of the most poorly understood, with only a handful of species discovered in the past hundred years. A newly identified one has been in our possession for decades without us even knowing.

A strange collection of unstudied bones - on show at Australia's oldest museum for years - has turned out to be an entirely new dinosaur species and the first evidence of a dinosaur herd in the country, including the most complete opalised dinosaur skeleton in the world.

"This is unheard of in Australia," lead author Phil Bell told The Smithsonian. "There were around 60-odd bones in the entire collection, which is a remarkable number for an Australian dinosaur."

Preserved in opal, the glittering remains were first discovered in 1984 by Australian miner Bob Foster, who worked in an outback town and fossil hotspot named Lightning Ridge.

Frustrated by the number of dinosaur bones he was finding (after all, his livelihood was based on opals), Foster made the long trip to the Australian Museum in Sydney, over 800 kilometres away.

"I was a bit tired by then," he told The New York Times. "I'd carried these suitcases on the train, and the bus, and up the stairs, and I opened them and threw the bones all out on the table and they were diving to catch them before they landed on the floor."

(Robert A Smith/Australian Opal Centre)

(Robert A Smith/Australian Opal Centre)

And then, for some inexplicable reason, the biggest collection of opalised dinosaur fossils went completely unstudied. When Foster spotted some of them on display at an opal store in Sydney many years later, he took back what he could and donated it all to the Australian Opal Centre in 2015.

It was here that the first formal study truly began. After years of careful research, using a CT scanner instead of physical extraction, researchers at the University of New England in Armidale have discovered traces of an entirely unknown species of dinosaur, called Fostoria dhimbangunmal, named for its discoverer and the traditional land on which it was found.

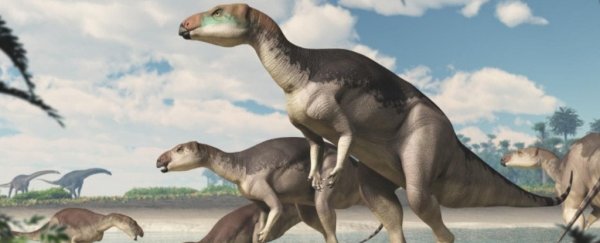

Encrusted in opal, the remains likely belong to four plant-eating dinosaurs that are related to the iguanodontian dinosaur. Diverse during the early Cretaceous, this taxa of dinosaurs has so far been found mostly in Europe and North America.

Fostoria is only the second one described in Australia, and also the youngest. Unlike its Australian peer, up in central Queensland, the bone bed where these fossils were found - which used to be a lush floodplain of lakes and rivers - is stratigraphically higher.

As such, the authors estimate that these dinosaurs once roamed the eastern margin of Australia's inland sea, which existed during the mid-Cretaceous, when Australia was part of the supercontinent Gondwanaland.

The opalised fossils support earlier claims that this particular taxa of dinosaur, which had a horse-shaped skull and a kangaroo-like body, was more geographically widespread than we once thought.

(Bell, Vertebrate Paleontology, 2019)

(Bell, Vertebrate Paleontology, 2019)

When Australia's inland sea started disappearing, roughly 100 million years ago, the drying sandstone near Lightning Ridge started growing in acidity, releasing silica which then slowly hardened into opal.

When this glittering substance becomes trapped in the dips and pockets of decayed dinosaur bones, it creates a shimmering mould of ancient remains.

Based on four of these opal-encrusted fossils found near Lightning Ridge, the authors argue that the Foster collection belongs to a herd of at least four different-sized animals, including two large individuals up to 5 metres in length (16 feet), one 'mid'-sized animal, and a small individual.

Other than their size, the only clear indication of these dinosaurs' age was a single, unfused mid-caudal neural arch, which suggests that one of the smaller animals had not yet reached skeletal maturity.

"We have bones from all parts of the body, but not a complete skeleton," Bell told National Geographic. "These include bones from the ribs, arms, skull, back, tail, hips, and legs. So, it's one of the most completely known dinosaurs in Australia … [with] 15 to 20 percent of the skeleton of the species."

Now imagine all of those invaluable dinosaur fossils, sitting behind glass in an opal store, languishing for decades.

The research has been published in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.