Done with putting up with abdominal cramping for more than a week, a 37 year old woman from the French island of Réunion east of Madagascar visited a hospital emergency department, only to discover she was – in fact – pregnant.

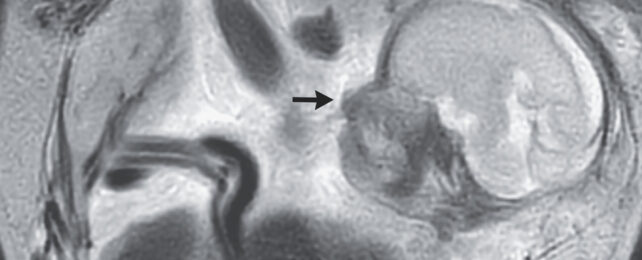

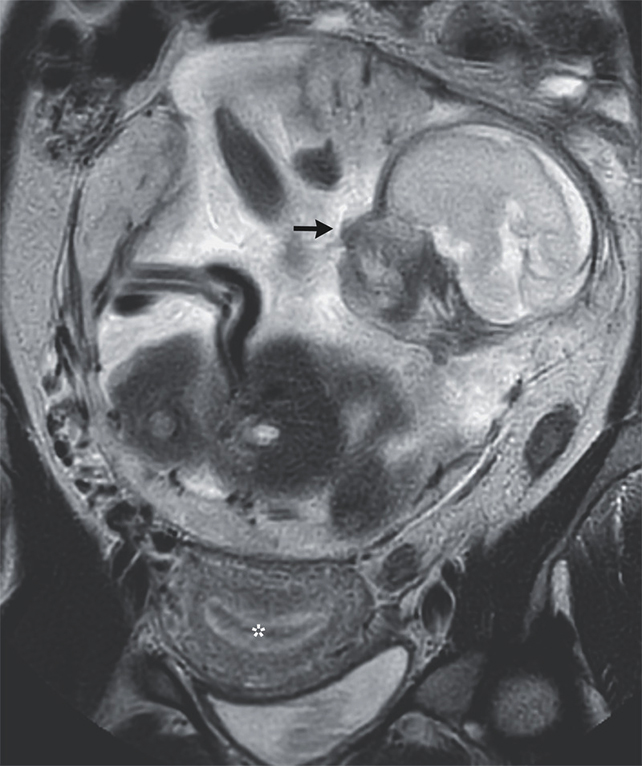

Scans soon revealed a rather surprising twist. Though there was a 23-week-old baby happily kicking around inside the woman's body, her uterus was completely empty. The fetus had instead set anchor to the membrane lining the abdominal cavity, just above the mother's tailbone.

Identifying the situation as a case of abdominal ectopic pregnancy, the woman's medical care team sent her to a more suitable hospital, where at 29 weeks the baby was delivered surgically and placed into neonatal intensive care. Around 2 months after being delivered, the child was given the all-clear to go home.

The uterus is a finely-tuned marvel of biology, adapted to protect and nurture a fertilized egg until the fetus is strong enough to survive the outside world.

In around one out of every hundred pregnancies, however, the fertilized egg finds itself heading along a completely different route, forgoing the womb's warm embrace to nestle into tissue that's far less suitable for its development.

Most ectopic pregnancies implant themselves into the lining of one of the two fallopian tubes that channel ova from the ovaries, resulting in a potentially life-threatening situation should the embryo continue to grow. Without suitable medical care, as many as 10 percent of such pregnancies can claim the parent's and child's lives.

Yet in less than one percent of ectopic pregnancies, the newly-formed embryo drifts out of the uterus's internal environment altogether and into the abdominal cavity, where it settles against the peritoneal membrane, spleen, or some other tissue or organ, and weaves itself a placenta.

Surprisingly, this arrangement isn't always as disastrous for the embryo as it seems. At least, not at first. Sooner or later, however, the unsupported weight of the growing child and pressure of surrounding organs pose risks to both the child's development and their parent's health.

Maternal death beyond 20 weeks of gestation can occur in as many as nearly one in five cases thanks to shock, hemorrhaging, and multiple organ failure.

For the woman in this case, a timely visit to the emergency department almost certainly saved her life. An ultrasound and MRI showed that though her uterus's lining was fully prepared to support a growing embryo, nobody was home.

While the placenta's arteries were plugged and part of the organ was removed during the operation to deliver her child, it took a follow-up procedure 12 days later for the rest of the tissue to be carefully removed.

Just what causes embryos to undergo such rare and unusual migrations isn't clear. Studies on ectopic pregnancies in general suggest a history of previous cases can raise the risk of it reoccurring, while some sexually transmitted infections, endometriosis, and pelvic inflammatory disease may also play a role.

A case study reports that, having had two full-term vaginal deliveries, one miscarriage, and no previous surgeries or relevant infections, the patient has no medical history that might help explain her own unusual pregnancy.

According to the case study, both mother and child were doing relatively well at the time of departing the tertiary care hospital that delivered the newborn – a rare happy ending for a serious medical condition that affects a tiny proportion of all pregnancies.

While the patients were lost to follow-up, we might assume they both returned home with one amazing story to share.

This case study was published in the New England Medical Journal.