In a surprise discovery, scientists have found that bacteria see the world in effectively the same way as humans, with bacterial cells acting as the equivalent of microscopic eyeballs.

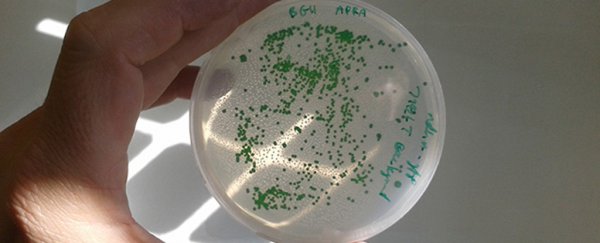

British and German researchers made the finding by accident when studying aquatic cyanobacteria, which sometimes form a green film on rocks and pebbles. Scientists already knew the bacteria could perceive the position of a light source and move towards it – a phenomenon called phototaxis – but before now, no one understood how they did it.

"We noticed it accidentally, because we had cells on a surface and we were shining light from one side, in order to watch the movement towards the light," microbiologist Conrad Mullineaux from Queen Mary University of London told Jonathan Webb at BBC News. "We suddenly saw these focused bright spots [inside the cells] and we thought, 'bloody hell!' Immediately, it was pretty obvious what was going on."

What the researchers discovered when studying Synechocystis – a species of cyanobacteria found in freshwater lakes and rivers – is that their cell bodies act like a lens. When light hits the spherical surface of the cell, it refracts into a point on the other side of the cell. This triggers movement by the cell away from the focused internal spot, towards the source of the light, with the cells using tiny tentacle-like structures called pili to pull themselves forwards.

What's amazing is that scientists have been studying bacteria for centuries without realising this functional resemblance of the cell body to an eyeball or camera lens. What's more, when Mullineaux and his colleagues did happen to notice it, they did so by chance in an incredibly small organism, which measures just 3 micrometres (0.003 mm) in diameter.

eLife

eLife

"Our observation that bacteria are optical objects is pretty obvious with hindsight, but we never thought of it until we saw it," said Mullineaux in a press release. "And no-one else noticed it before either, despite the fact that scientists have been looking at bacteria under microscopes for the last 340 years."

The findings, published in eLife, don't mean bacteria perceive the world with equal powers of vision to humans – just that the light-based lens mechanism works in the same way.

According to the researchers, a Synechocystis cell is about half a billion times smaller than the human eye, and its much lower resolution would only enable a blurred outline of objects to be made out.

"The physical principles for the sensing of light by bacteria and the far more complex vision in animals are similar, but the biological structures are different," said one of the team, Annegret Wilde from the University of Freiburg in Germany.

But it's a vital trick for the bacteria. Without sensing light and moving toward it, the organisms wouldn't be able to photosynthesise, which has been crucial to their survival since time immemorial.

"This was a mechanism that was missing. We didn't know it and it's a very elegant demonstration – and surprising," Gaspar Jekely, a researcher from the Max Planck Institute for Developmental Biology in Germany, who was not involved with the research, told the BBC. "Cyanobacteria are 2.7 billion years old, so it's much older than any animal eye. Presumably, this mechanism has existed for a very long time."