When you're trying to figure out what alien life might look like, it makes sense to be looking in the most extreme environments Earth has available.

One such place where life has been found to thrive is three kilometres (1.86 miles) beneath the ground, the home of one of the strangest lifeforms we know: the bacterium Desulforudis audaxviator.

It lives in complete dark, in groundwater up to 60 degrees Celsius (140 Fahrenheit) - an environment devoid of sunlight, oxygen or organic compounds.

And it has perfectly evolved to derive its energy from the radioactive decay of uranium in the rocks around it - which means it lives off nuclear energy instead of relying on the Sun.

This, according to researchers from the Brazilian Synchrotron Light Laboratory and the University of São Paulo, makes it an excellent model for studying the possibility of extraterrestrial life.

In particular, the possibility of life on Jupiter's moon Europa, an ocean planet covered in ice, far from the life-giving light and warmth of our home star.

"We studied the possible effects of a biologically usable energy source on Europa based on information obtained from an analogous environment on Earth," principal investigator Douglas Galante told the Brazilian news agency FAPESP.

Previously, NASA has proposed that Europa may have Earth-like hydrothermal vents - holes in the seafloor spewing heat, around which life clusters far from sunlight. But those lifeforms around hydrothermal vents still use oxygen in the water, produced by organisms closer to the surface.

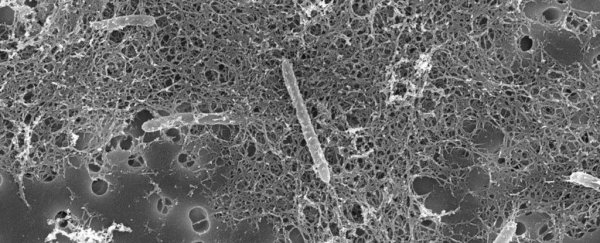

Desulforudis audaxviator goes one step further. Discovered in 2008, it was the only bacterium found in samples of groundwater from underground in the Mponeng gold mine in South Africa, where it has lived for millions of years.

It was totally alone in its ecosystem - it doesn't even feed on any other species.

"This very deep subterranean mine has water leaking through cracks that contain radioactive uranium," Galante explained.

"The uranium breaks down the water molecules to produce free radicals. The free radicals attack the surrounding rocks, especially pyrite, producing sulfate. The bacteria use the sulfate to synthesise ATP [adenosine triphosphate], the nucleotide responsible for energy storage in cells.

"This is the first time an ecosystem has been found to survive directly on the basis of nuclear energy."

In their paper, the team determined that the conditions under which Desulforudis audaxviator has thrived for so long are also plausible on Europa.

There are three ingredients required to make Europa habitable, according to NASA. Water, which seems likely based on observations and models of the moon; heat; and the chemicals needed to feed the life.

Although it is far from the Sun, it is quite possible that there is heat in the Europan oceans. This is because its orbit around Jupiter is elliptical, which means the tidal forces acting upon it are stronger at certain points in the orbit.

Europa deforms when it's at those points, which creates internal friction, generating heat in turn.

The chemistry is the part that's hardest to confirm, since we don't currently have a means of sampling Europa's waters. But, based on the presence of radioactive materials in the Solar System, it's possible they exist on Europa, too.

"Their presence had been detected and measured on Earth, in the meteorites that come to Earth, and on Mars. So we can say with some certainty that this must have occurred on Europa as well," Galante said.

"In our study, we worked with three radioactive elements: uranium, thorium and potassium, the most abundant in the terrestrial context. Based on the percentages found on Earth, in meteorites and on Mars, we can predict the amounts that probably exist on Europa."

They were able to show that radioactive materials could exist on Europa in sufficient quantities to support life based on what we know of Desulforudis audaxviator - provided there's enough pyrite to produce the necessary sulfate.

NASA is planning to send a spacecraft to Europa to help find the answers to these questions, and many others. The Europa Clipper will be launching between 2022 and 2025, and will orbit Jupiter to follow up observations of Europa made by the Galileo spacecraft.

"The ocean bed on Europa appears to offer very similar conditions to those that existed on primitive Earth during its first billion years. So studying Europa today is to some extent like looking back at our own planet in the past," Galante said.

"In addition to the intrinsic interest of Europa's habitability and the existence of biological activity there, the study is also a gateway to understanding the origin and evolution of life in the Universe."

The team's paper has been published in Nature.