It's one of the biggest questions in science: to what extent are we defined by our genetics? A new analysis of Ludwig van Beethoven's DNA, showing a low predisposition for beat synchronization, hints that we can become much more than our genes suggest.

In other words, the celebrated German composer's musical talents reached far beyond what you might expect from his genetics, according to the international team of researchers behind the new study.

There's lots to take away here, including the limitations of what we can find out about someone's genetics, how those genetics end up affecting our lives, and how music and creativity are a complex mix of all kinds of factors.

"Before running any analysis, we preregistered the study, and emphasized that we had no prior expectation about what Beethoven would score," says cognitive neuropsychologist Laura Wesseldijk from the Max Planck Institute for Empirical Aesthetics (MPIEA) in Germany.

"Instead, our aim was to use this as an example of the challenges of making genetic predictions for an individual that lived over 200 years ago."

Genetic material was extracted from preserved strands of Beethoven's hair, and the resulting DNA coding was given a polygenic score: a summarized estimate of how genetic variants might manifest in traits or behaviors.

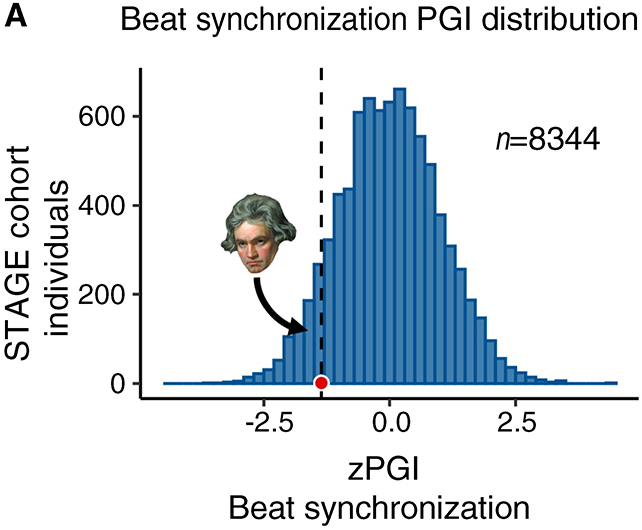

Beat synchronization ability – being able to recognize and keep time with a beat – is one of these traits, and it's previously been linked to music ability in general. However, Beethoven's score in this area was nothing out of the ordinary.

The researchers say the results aren't all that unexpected. They highlight both the limits of polygenic scores and their uses, particularly when it comes to picking out one individual (and an exceptional individual, at that).

"You should be skeptical if someone claims they can use a genetic test to reliably determine whether your child will be musically gifted – or especially talented in some other area of behavior," says Simon Fisher, a professor of language and genetics at the MPIEA.

This kind of genetic analysis is useful for studying population-wide trends in behavior tied to a specific time and place. But once we hone things down to a single individual, too many other factors, like changing environmental influences, come into play to draw reliable conclusions.

For example, the environmental conditions of modern Western society that may help drive the current association seen between this gene and musicality may not have been present in Beethoven's time.

But genetic analyses can be individually useful in other ways: a previous study of Beethoven's DNA, for example, identified a genetic predisposition for liver disease, which may have affected his health more than any of his lifestyle choices.

Earlier studies have indicated we might inherit around 42 percent of our musicality through the genes we get from our parents. The debates over nature vs nurture continue, but in the meantime, maybe don't give up on the piano lessons just yet.

"Obviously, it would be wrong to conclude from Beethoven's low polygenic score that his musical abilities were unexceptional," says Fisher.

"We think that the big mismatch between this DNA-based prediction and Beethoven's musical genius provides a valuable teaching moment."

The research has been published in Current Biology.