Being unrealistically optimistic might endear a person to those around them, but the risky behavior that comes from it may not always follow sage advice. Now a new study has linked higher levels of financial optimism with lower levels of cognitive ability.

The research was carried out by Chris Dawson, a behavioral economist at the University of Bath in the UK. Dawson looked at the survey responses of 36,312 individuals in the UK, comparing their expectations about how their household finance situation would change over 12 months with the reality of what actually happened.

Five measures of cognitive ability were also collected, testing word recall, verbal fluency, working memory, abstract thought, and math ability. Certain sociodemographic and socioeconomic controls were applied to the results, to allow for variations in age, gender, marital status, household size, and other factors.

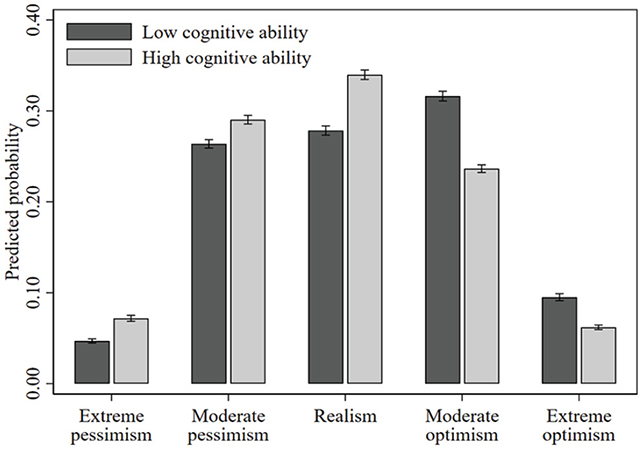

The results revealed a link between cognitive ability and how optimistic or pessimistic someone was: those who scored highest on cognitive ability were 38.4 percent less likely to have an optimistic mindset and 53.2 percent more likely to have a pessimistic mindset, compared to those who scored the lowest.

Those who scored highest on cognitive tests were also 22 percent more likely to be realists, who are considered the most objective about situations, not leaning too positive or negative.

"This suggests that the negative consequences of an excessively optimistic mindset may, in part, be a side product of the true driver, low cognitive ability," writes Dawson in his published paper.

As a species, we generally tend to be overly optimistic about some parts of our lives, such as how long we're going to live or how much money we're going to earn. That unrealistic mindset can lead to bad decisions – not saving enough for retirement, for example.

It also comes with some benefits: previous research has suggested that optimism is better for our health, or at least certain parts of it. A sunnier disposition encourages the people we come into contact with as well.

While forecasting the future is admittedly difficult, it's clearly in our own interests to be realistic about financial planning, and in this realm at least, pessimists are more likely to have higher cognitive ability while optimists lower cognitive ability.

It's important to note that the data collection and subsequent results aren't comprehensive enough to prove a causal relationship – that one factor directly affects another – but there seems to be an association here that's worth investigating.

The study suggests that smarter people may be better able to keep unrealistic optimism in check, and more capable when it comes to assessing information honestly.

It's an approach that might lead to a less cheerful mood in the short term, but better decision-making in the long term – all areas that could be looked at in future research.

"While unrealistic optimism about household finances is a very specific measure of optimism, to the extent to which unrealistic optimism is domain-general, cognitive ability could also explain why optimists fail to take precautionary actions outside the realm of finance, like quitting smoking," writes Dawson.

The research has been published in Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin.