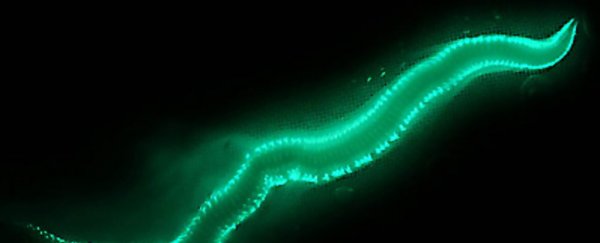

If you're in Bermuda at the right time of the month, you're in for a treat. Around 2-5 days after the full moon, and around 55 minutes after sunset, the Bermuda fireworm swims to the ocean surface and flares into brilliance, lighting up with an incredible bioluminescent glow.

The creature lives most of its life in mucus tubes in the seabeds, but when it comes time to mate, the fireworm puts on the fireworks.

Now, a new gene study reveals where this spectacular light show comes from. The enzyme responsible for the glow of the fireworm - Odontosyllis enopla - is unique, unlike those found in any other bioluminescent creature.

It's how the female worm attracts a mate, and it occurs year round, although much more strongly in summer and early autumn.

She swims around in a circle, releasing a bright green glowing chemical in order to attract the males on the seabed to swim up to her, also glowing brightly.

"The female worms come up from the bottom and swim quickly in tight little circles as they glow, which looks like a field of little cerulean stars across the surface of jet black water," said invertebrate zoologist Mark Siddall of the American Museum of Natural History.

"Then the males, homing in on the light of the females, come streaking up from the bottom like comets - they luminesce, too. There's a little explosion of light as both dump their gametes in the water. It is by far the most beautiful biological display I have ever witnessed."

Christopher Columbus himself noted the phenomenon, when he observed it while sailing by on 11 October 1492, noting that it resembled "the flame of a small candle alternately raised and lowered," but the luminescence wasn't connected to the fireworms until the 1930s.

It's now thought that they choose this precise time because to mate there's no Moon in the sky in the early evening, which makes the females' glow easier for the males to see.

But no one knows for sure. "It's like they have pocket watches," said one of the researchers, biologist Mercer R. Brugler of the American Museum of Natural History.

To investigate the bioluminescence, the research team studied something called the transcriptome of a dozen female fireworms. This is the animal's full set of RNA molecules, which are often involved in encoding the proteins associated with bioluminescence.

They found - as expected - that the fireworms glow because they produce a specific class of bioluminescent enzyme, called a luciferase. Many creatures produce these enzymes to glow, including fireflies, bacteria, and marine creatures such as copepods.

Firefly luciferase has also been introduced into other species - such as mice and plants - to cause them to glow.

But the research team found that the luciferase found in the Bermuda fireworm is distinct from any other luciferase known to date. They compared it to luciferases in publicly available datasets, and found no identifiable homologous proteins among other bioluminescent species.

This is pretty cool, because it opens new research avenues.

"It's particularly exciting to find a new luciferase because if you can get things to light up under particular circumstances, that can be really useful for tagging molecules for biomedical research," said biologist Michael Tessler of the American Museum of Natural History.

But what about the worms' sense of time? The researchers looked into that too. They still don't know how the wee beasties know what time of the month it is, but they did make some cool discoveries.

They found that the nephridia, an organ that stores and releases gametes, enlarges just prior to swarming.

They also found that the worms' four eyes become enlarged, and heavily pigmented in this pre-mating period - all the better to see you with my dear!

There was, however, no evidence of tiny worm pocket watches.

The team's research has been published in the journal PLOS One.