Scientists researching a key aspect of biochemistry in living creatures have been taking a very close look at the tiny Caenorhabditis elegans roundworm. Their latest results show that when these nematodes get put under more biochemical stress early in their lives, they somehow tend to live longer.

This type of stress, called oxidative stress - an imbalance of oxygen-containing molecules that can result in cellular and tissue damage - seems to better prepare the worms for the strains of later life, along the same lines as the old adage that whatever doesn't kill you, makes you stronger.

You might think that worm lifespans have no bearing on human life. And surely, until we have loads more research done in this field, it would be a big leap to say the same principles of prolonging one's lifespan might hold true for human beings.

But there's good reason to put C. elegans through the paces. This model organism has proven immensely helpful for researchers trying to better understand key biological functions present in worm and human alike - and oxidative stress is one such function.

The little wriggly creatures are known to have significant variations in their lifespan even when the whole population is genetically identical and grows up in the exact same conditions. So the team went looking for other factors that affect C. elegans' longevity.

"The general idea that early life events have such profound, positive effects later in life is truly fascinating," says biochemist Ursula Jakob from the University of Michigan.

Jakob and her colleagues sorted thousands of C. elegans larvae based on the oxidative stress levels they experienced during development – this stress arises when cells produce more oxidants and free radicals than they can handle. It's a normal part of the ageing process, but it's also triggered by exercise and a limited food supply.

One way to measure this stress is by the levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) molecules an organism produces - simply put, this measurement indicates the biochemical stress an organism is under. In the case of these roundworms, the more ROS were produced during development, the longer their lifespans turned out to be.

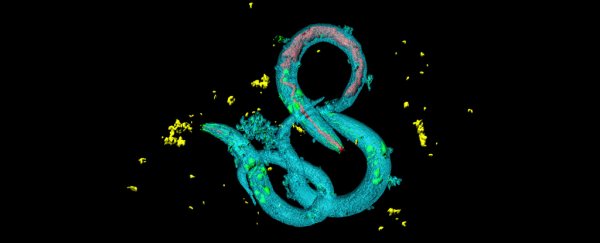

(University of Michigan)

(University of Michigan)

To explain how this effect of ROS might come about, the researchers went looking for changes in the worms' genetic regulation, specifically those genes that are known to be involved in dealing with oxidative stress.

While doing so, they detected a key difference - the nematodes exposed to more ROS during development appeared to have undergone an epigenetic change (a gene expression switch that can happen due to environmental influences) that increased the oxidative stress resistance of their body's cells.

There are still a lot of questions to answer, but the researchers think their results identify one of the stochastic – or random – influences on the lifespan of organisms; it's something that has been hypothesised in the field of the genetics of ageing. And down the line, it may turn out to be relevant for ageing humans, too.

"This study provides a foundation for future work in mammals, in which very early and transient metabolic events in life seem to have equally profound impacts on lifespan," the researchers conclude.

The study has been published in Nature.