Magpies and crows are using anti-bird spikes collected from buildings to build nests.

These long metal rods are intended to discourage birds from hanging around, but some crafty urban avians in Europe have found ways to take advantage of the deterrent.

"It's actually like a joke," says biologist Auke-Florian Hiemstra of Naturalis Biodiversity Center in the Netherlands, "even for me as a nest researcher, these are the craziest bird nests I've ever seen.

Ironically, this first-of-its-kind Dutch study on bird nests made almost entirely of these materials found magpies using the spikes for their original purpose: to ward off birds.

Hiemstra and his colleagues describe all known anti-bird spike nests of carrion crows (Corvus corone) and Eurasian magpies (Pica pica).

Bird nests made from anti-bird spikes! 🤯 Even for me as a nest researcher, these are the craziest bird nests I've ever seen. Today my paper came out on this rebellious behaviour. And it's like telling a joke...

— Auke-Florian (@AukeFlorian) July 11, 2023

A thread. 🧵 pic.twitter.com/X8dTZICS34

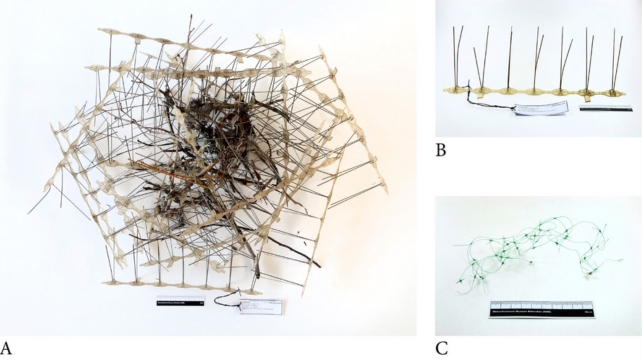

They discovered two examples of these nests in Rotterdam, the Netherlands. A crow's nest with at least 16 anti-bird spikes was found in a poplar tree in 2009, and an unfinished crow's nest in a weeping willow that was pruned in 2021.

That intriguing structure had 336 spikes that extended almost 8 meters (26.2 feet), and all had traces of the adhesive used to glue strips to buildings, suggesting they were forcefully removed. The nest even had a piece of anti-bird net, another amusingly ineffective bird deterrent.

Crows can use anti-bird spikes to construct nests, then magpies' ability to put them to their intended use is even more impressive.

The roof of a magpie nest found in a sugar maple tree in Antwerp, Belgium, in 2021 is almost entirely made of metal anti-bird spikes, with 61 strips totaling 604 spikes and 16.72 meters of strips. Placement within the domed roof suggests a more specific use: to protect them from aerial attacks.

Magpie eggs and babies are a tasty snack for crows, who sometimes try to stop magpies from building these characteristic domed shapes on top of their nests.

In an apparent attempt to deter crows, magpies use thorny twigs to build the roof, traveling some distances to collect suitable materials.

So Hiemstra and his team think these sharp anthropogenic materials may be used specifically to improve nest defense. Urban magpies might use the strips to replace thorny twigs, which are less plentiful in cities.

Another magpie nest found in Glasgow, Scotland, in 2021 had about 12 anti-bird spikes in the top. A third magpie nest with metal and plastic anti-bird spikes was found in an ornamental plum tree in Enschede, the Netherlands, in 2023.

Anti-bird spikes can secure twigs and support nest structure, so scientists think they could be rather useful nesting material.

The adaptability of birds has been displayed before through their use of human-made materials like nails and screws, barbed wire, and even discarded syringes.

A sulphur-crested cockatoo (Cacatua galerita) in Australia's Blue Mountains was caught on video in 2019, taking great delight in ripping off anti-bird spikes from a building. This is far from the only technique these particular creatures have 'up their wings' to mess with humans.

As the team notes, more anthropogenic material than natural biomass exists these days, so urban birds adopting these spiky substitutes is not surprising. But this accumulating human-made stuff can harm birds too.

Another new study, part of a 20-paper-themed issue, found 176 bird species use human-made material in their nests, with pros and cons.

Evolutionary biologist Zuzanna Jagiełło from the University of Warsaw and the lead author of the research says, "This is worrying because it is becoming increasingly apparent that such materials can harm nestlings and even adult birds."

Birds can become fatally entangled in twine, and bright colors on human-made materials help predators to find and attack nests.

Compounds from cigarette butts repel parasites from birds' nests but increase chromosomal abnormalities. And parents mistakenly feed the butts to their babies, with effects similar to plastic ingestion.

So if even materials designed to discourage building nests could end up in a bird's nest, we should do our best to minimize harm to these clever critters.

"This innovative use of bird spikes for nest construction…" Hiemstra and colleagues write, "shows the flexibility of nest-building behavior and use of materials."

The research is published in Deinsea, the online journal of the National History Museum Rotterdam.