As if cracking open a cosmic Russian nesting doll, astronomers have peered into the center of the Milky Way and discovered what appears to be a miniature spiral galaxy, swirling daintily around a single large star.

The star – located about 26,000 light-years from Earth near the dense and dusty galactic center – is about 32 times as massive as the sun and sits within an enormous disk of swirling gas, known as a "protostellar disk". (The disk itself measures about 4,000 astronomical units wide – or 4,000 times the distance between Earth and the Sun).

Such disks are widespread in the universe, serving as stellar fuel that help young stars grow into big, bright suns over millions of years.

But astronomers have never seen one like this before: a galaxy in miniature, orbiting perilously close to the center of our own galaxy.

How did this mini-spiral come to be, and are there more like it out there?

The answers may lie in a mysterious object, about three times as massive as Earth's sun, lurking just outside the spiral disk's orbit, according to a new study published May 30 in the journal Nature Astronomy.

Using high-definition observations taken with the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) telescope in Chile, the researchers found that the disk doesn't appear to be moving in a way that would give it a natural spiral shape.

(SHAO)

(SHAO)

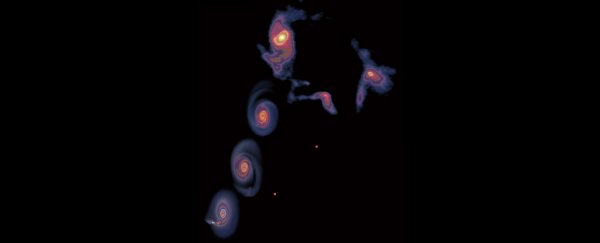

Above: A schematic view of the history of the accretion disk and the intruding object. The three plots starting from the bottom left are snapshots from a numerical simulation, showing the system at the time of the flyby event, 4,000 years later, and 8,000 years after the event. The top right image was captured from ALMA observations, showing the disk with spirals and two objects around it, corresponding to the system 12,000 years after the event.

Rather, they wrote, the disk seems to have been literally stirred up by a near-collision with another body – possibly the mysterious triple-sun-sized object that's still visible nearby it.

To check this hypothesis, the team calculated a dozen potential orbits for the mysterious object, then ran a simulation to see if any of those orbits could have brought the object close enough to the protostellar disk to whip it into a spiral.

They found that, if the object followed one specific path, it could have skimmed past the disk about 12,000 years ago, perturbing the dust just enough to result in the vivid spiral shape seen today.

"The nice match among analytical calculations, the numerical simulation, and the ALMA observations provide robust evidence that the spiral arms in the disk are relics of the flyby of the intruding object," study co-author Lu Xing, an associate researcher from the Shanghai Astronomical Observatory of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, said in a statement.

Besides offering the first direct images of a protostellar disk in the galactic center, this study shows that external objects can whip stellar disks into spiral shapes typically only seen on the galactic scale.

And because the center of the Milky Way is millions of times denser with stars than our neck of the galaxy, it's likely that near-miss events like this occur in the galactic center pretty regularly, the researchers said.

That means our galaxy's center may be overloaded with miniature spirals, only waiting to be discovered. Scientists may not reach the center of this cosmic nesting doll for a long, long time.

Related Stories:

The 15 weirdest galaxies in our universe

The 12 strangest objects in the universe

9 ideas about black holes that will blow your mind

This article was originally published by Live Science. Read the original article here.