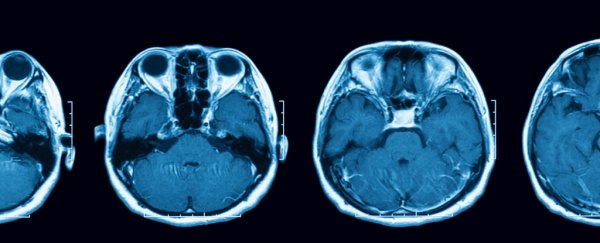

Preliminary MRI scans have shown some women on the birth control pill have different sized brain structures, and while that might sound freaky, that's no reason to stop taking the medication.

It's still unclear whether these changes in brain volume are linked to the hormonal pill. And if they are, is that causing negative irreversible effects? We don't have enough evidence to say.

Even though roughly 100 million women use the oral contraceptive pill worldwide, remarkably few studies have looked at how these synthetic hormones affect brain structure and function. In fact, it's hardly been investigated at all, and the results we currently have are mixed.

Compared to naturally cycling women, some research has shown women on the pill have a larger hippocampus, fusiform gyrus, and cerebellum, while other studies have reported changes in the prefrontal cortex and the amygdala.

Now, researchers are throwing the hypothalamus into the mix, too. This is a structure near the base of the brain that helps produce hormones and regulate bodily functions like temperature, mood, appetite, sex drive, sleep and heart rate.

"There is a lack of research on the effects of oral contraceptives on this small but essential part of the living human brain," said neuroscientist Michael Lipton at a recent conference.

"We validated methods for assessing the volume of the hypothalamus and confirm, for the first time, that current oral contraceptive pill usage is associated with smaller hypothalamic volume."

The authors go on to suggest that oral contraceptives are somehow interfering with the hypothalamus' typical hormone release and that's why it's shrinking. But there's currently no evidence to support that idea and these results are only preliminary.

The sample size of the study was quite small, including only 50 women, 21 of whom were on the birth control pill, and the findings are, as yet, un-peer reviewed.

Nevertheless, when comparing overall brain volume, the researchers report a 6 percent decrease in the size of the hypothalamus among women who took birth control.

For the brain, Lipton claims, this is a "dramatic difference", and while it's certainly something that warrants more research, how we convey these results to users of the pill is really important.

Neuroendocrinologist Nicole Petersen, who was not involved in the study but who does similar research, told Discover Magazine that her ultimate question is, "So what?"

"Assuming this finding is a true finding, what does it mean for a woman whose hypothalamus is made smaller by oral contraceptives?" asks the University of California Los Angeles researcher.

If it does mean anything, it's been really good at avoiding our attention in clinical trials. Last year, ScienceAlert reported on a study that suggested oral contraceptives could have an impact on social judgement, but only a very small one.

"If oral contraceptives caused dramatic impairments in women's emotion recognition, we would have probably noticed this in our everyday interactions with our partners," cognitive psychologist Alexander Lischke explained at the time.

The same could also be said for any potential effects of hypothalamus shrinkage. And it must be remembered that Lipton's research found no significant correlation between hypothalamic volume and cognitive performance.

So in the end, these changes in the brain may not be anything to worry about. In fact, they might not even be caused by oral contraceptives.

Previous findings on brain volume and oral contraceptives are inconsistently replicated and long-term results are still lacking. Until an incontrovertible cause-and-effect is found, it doesn't make sense to freak out and stop taking the pill.

"Women should not be too concerned about these associations, as there currently is not enough information to change hormonal contraceptive use based on this and similar studies," University of Southern California gerontologist Alexandra Herrera, who was not involved in the study, told Gizmodo.

The new findings were presented at the Radiological Society of North America.