In limestone caverns beneath a Mexican forest, pitch-black ponds are home to strange, eyeless fish with taste buds all over their faces.

Known as blind cavefish, they are born with vestigial eyes, but some populations lose even those relics as they grow up. By adulthood, their empty eye sockets are filled with fat deposits and covered with scales.

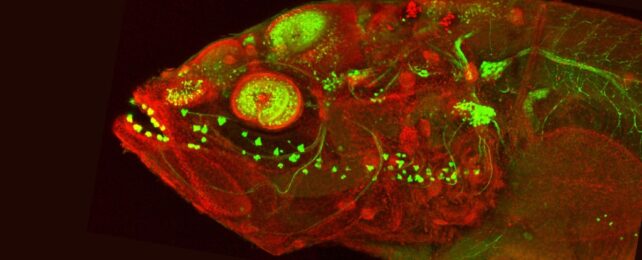

According to a new US study, that isn't the only odd facial transformation a growing cavefish might experience. At birth, their taste buds resemble those of surface-dwelling relatives, the researchers found, but soon further taste buds begin to appear in more places – including the face and chin.

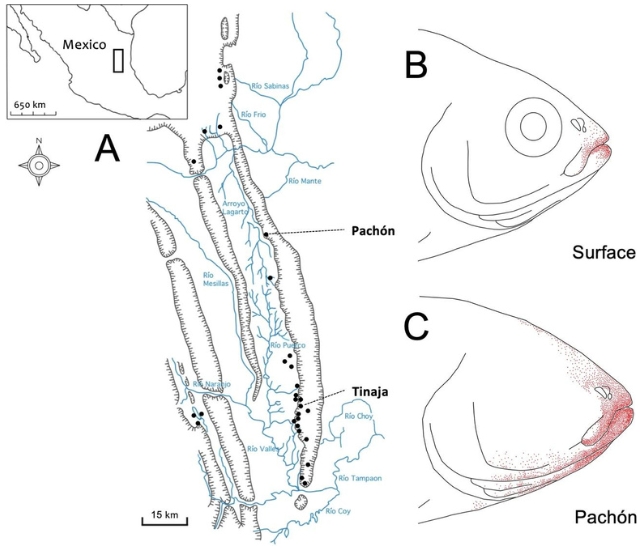

Blind cavefish are not a distinct species, despite their distinctive appearance. They're classified as Mexican tetra (Astyanax mexicanus), along with close relatives inhabiting nearby streams and rivers on the surface.

Unlike the pale, eyeless cavefish, surface tetra have silvery scales and large, round eyes. The two remain genetically similar, though, easily interbreeding and producing fertile offspring.

The cave morphs likely arose multiple times via convergent evolution, previous research suggests, with surface fish colonizing various caves to form isolated populations, which then made similar adaptations to similarly dark conditions.

Their eyelessness is also an example of regressive evolution, or loss of a complex feature, that often occurs in cave-dwelling animals. Many cave creatures also evolve augmented non-visual senses, yet less is known about how exactly that works.

"Regression, such as the loss of eyesight and pigmentation, is a well-studied phenomenon, but the biological bases of constructive features are less well understood," says senior author Joshua Gross, a biologist at the University of Cincinnati.

Scientists first reported extra taste buds on the heads and chins of blind cavefish in the 1960s, but that initial discovery was not followed by further study of the genetic or developmental mechanisms enabling the phenomenon, according to Gross and his colleagues.

For the new study, they hoped to reveal when in a cavefish's life the extra taste buds appear. They focused on two separate populations, from the Pachón and Tinaja caves in northeastern Mexico's Sierra de El Abra region, where cavefish are known to possess the trait.

Their observations showed few differences in taste buds between surface fish and cave morphs for the first four months of life, followed by a significant change in cavefish at about five months old.

At that point, cavefish taste buds began to grow both in number and distribution, spreading beyond the mouth onto the head and chin. This process continued into adulthood, with taste-bud counts still rising for some fish after 18 months.

These cavefish are known to live well past 18 months in the wild and in captivity, and they may continue amassing taste buds on their faces as they age, the researchers note. In addition to shedding light on these mysterious fish, the study offers broader insights about evolution and sensory organ development.

"Knowing just how many doors this opened for future research involving taste bud and taste development was a truly rewarding aspect of this research, especially considering how long these fish live," says the study's first author, biologist Daniel Berning from the University of Cincinnati.

The taste-bud boom occurs at a life stage when cavefish are also shifting to different food sources. It corresponds with some populations' transition to eating bat guano, although it also happens to fish living in caves without bat populations.

Having more taste buds should give cavefish a more powerful sense of taste, which is probably adaptive, but there's still a lot we don't know.

"It remains unclear what is the precise functional and adaptive relevance of this augmented taste system," Gross says.

Research into cavefish taste is ongoing, however, with new studies examining how the fish respond to various flavors.

The study was published in Communications Biology.