We all need a way to get along in this wild, wicked world, and a rare insect found only on a mountainside on O'ahu has found an incredible strategy.

A species of caterpillar that scientists are calling the 'bone collector' is not only a carnivore, and a cannibal, it also dresses itself in the body parts of dead insects so it can sneak around undetected and steal prey right from the jaws of spiders.

No other species of caterpillar has been observed behaving this way, and only 62 individuals of the species have been seen in 20 years of fieldwork. The findings suggest that the newly described bone collector is rare, vulnerable, and requires targeted conservation to protect its place in our world.

The insect belongs to the Hyposmocoma genus, and has been described for the first time in a new paper.

Caterpillars are the larval stage for insects of the Lepidoptera order – you know, butterflies and moths. As adults, most of these insects primarily feed on plant matter (mostly), and their larvae do the same. It's common to see caterpillars merrily munching away on a leaf.

Carnivorous species are rare. Just 0.1 percent of the known butterfly and moth species have caterpillars that like to munch on other animals. Caterpillars aren't exactly the most nimble of creatures, so the food of carnivorous species often includes slow-moving or stationary prey such as scale insects that cling to trees, wasp and ant larvae, and the eggs of other insects.

The bone collector's strategy involves cozying up to a spider. A research team led by entomologist Daniel Rubinoff of the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa observed the species in the wild, and collected several specimens to observe their behavior in a laboratory setting. The way they live their lives is very strange for a caterpillar.

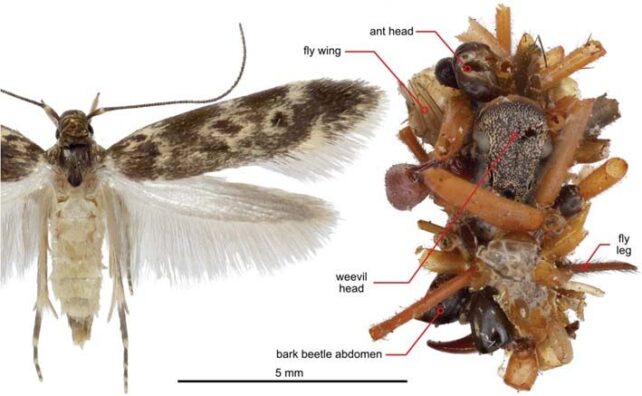

In the wild, a bone collector caterpillar will find an enclosed spider web – one that's safely concealed under tree bark, for example – and collect inedible pieces of insect to make themselves a little coat, bound together with silk.

Once there, they'll happily chow down on any insects caught in the web, even chewing through the silk wrappers of snacks that the spider has stashed for later.

The researchers found them living this way with multiple species of spiders, none of which were native to Hawaii, suggesting that the caterpillar is somewhat adaptable.

In the lab, the researchers gave the caterpillars a variety of detritus to choose from to build their little nests. The caterpillars noticeably only chose the body parts of other insects, or shed spider skin, eschewing bits of twig or leaf or bark. And when no insect parts were offered, the caterpillars did not accept anything else: it's bug bits or nothing.

"Given the context," the researchers write, "it is possible that the array of partially consumed body parts and shed spider skins covering the case forms effective camouflage from a spider landlord; the caterpillars have never been found predated by spiders or wrapped in spider silk."

In captivity, the caterpillars would eat any live, slow-moving, or immobilized insect prey. Anything was fair game – even each other. When placed together, one tore open the other's case, entered, and feasted on the inhabitant.

This probably helps reduce food competition, limiting each web to just one caterpillar interloper. But it also means that the species doesn't have strength in numbers.

Its genome suggests that it first emerged between around 15 million to 9 million years ago, older than the oldest island of Hawaii by millions of years, indicating that it was once more widespread.

Today, its range is just 15 square kilometers (5.8 square miles), isolated to a forest in a single mountain range, on a single island. Work needs to be done to understand this strange little caterpillar and how it developed its survival strategy… but also to protect it from increasing environmental stressors, including a growing number of invasive species in its tiny, isolated habitat range.

"Without conservation attention," the researchers write, "it is likely that the last living representative of this lineage of carnivorous, body part-collecting caterpillars that has adapted to a precarious existence among spider webs will disappear."

The research has been published in Science.