Ever suffered from fury blackouts? Uncontrollable, violent road rage? Those symptoms could be a sign of a condition called intermittent explosive disorder (IED) - and scientists have now shown that adults who experience it are more than twice as likely to have been exposed to the well-known 'cat parasite', toxoplasma gondii, than people without the condition.

Before you direct an angry outburst at your cat, keep in mind this study has only found a correlation between the two, which we all know by now does not equal causation. And just last month, scientists showed that toxoplasmosis has much less of an effect on our mental state than we'd been led to believe, so it's likely there are other things going on here. But the new research is important, because it could provide clues on how to help those with the disorder keep calm and reduce aggression.

"Our work suggests that latent infection with the toxoplasma gondii parasite may change brain chemistry in a fashion that increases the risk of aggressive behaviour," said lead researcher Emil Coccaro from the University of Chicago. "However, we do not know if this relationship is causal, and not everyone that tests positive for toxoplasmosis will have aggression issues."

IED is a surprisingly common condition that's characterised by impulsive and recurrent aggressive outbursts that are arguably more extreme than the situations that trigger them. For example, wanting to smash in the windscreen of the guy in front of you because he indicated too late, or setting fire to your date's front yard because he/she cancelled at the last minute.

An estimated 16 million Americans are affected by IED, but researchers still don't know much about it, including how it's caused, how to diagnose it properly, or whether it can be treated - which is why this new research is so interesting.

To find out more, Coccaro performed extensive psychiatric analysis on 358 adults and sorted them into three groups: one third had IED; one third had no history of psychiatric illness; and one third had some kind of mental health condition, but not IED.

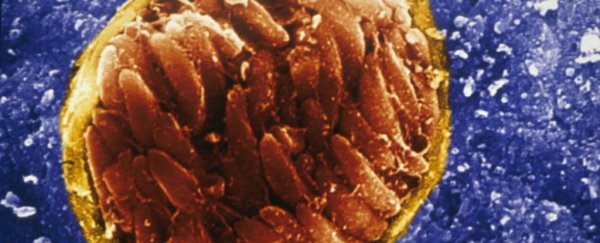

The team then used blood tests to measure which of them had been exposed to toxoplasmosis, a mostly harmless parasite that can be transmitted through undercooked meat, contaminated water, or the faeces of infected cats. It's estimated that around 30 percent of all humans have been infected, usually without any symptoms.

But some studies have - somewhat weakly - linked the presence of the parasite to reckless behaviour, depression, and schizophrenia, so the researchers thought they'd see whether it could also be associated with explosive rage.

They found that 22 percent of the IED group tested positive for toxoplasmosis exposure, versus only 9 percent of the healthy control group - which meant that those who experienced uncontrollable outbursts of anger were more than twice as likely to have been exposed.

Meanwhile, 16 percent of the third group (who had mental health conditions other than IED) tested positive for toxoplasmosis. And overall, the team found that people who'd been exposed to toxoplasmosis had higher scores of anger and aggression.

But it's important to note that this research didn't provide any insight into what could be causing this link, so it's still very early days. "We don't yet understand the mechanisms involved - it could be an increased inflammatory response, direct brain modulation by the parasite, or even reverse causation where aggressive individuals tend to have more cats or eat more undercooked meat," said one of the researchers, Royce Lee.

That said, it's a link worth following up on if we want to find better ways to cope with IED, and the researchers are now planning further studies on humans with the condition.

"It will take experimental studies to see if treating a latent toxoplasmosis infection with medication reduces aggressiveness," said Coccaro. "If we can learn more, it could provide rational to treat IED in toxoplasmosis-positive patients by first treating the latent infection."

The research has been published in The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. [Note: the journal site appears to be down right now]