Not all people with schizophrenia show the same abnormal brain structure, a new study has found.

Scanning the brains of over 300 schizophrenia patients, researchers now think they've identified two neuroanatomical subtypes of this mysterious neurological disorder; one of them has never been detected before, according to the team.

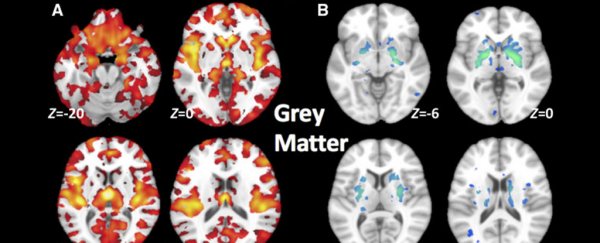

Today, the neurobiology of schizophrenia is poorly understood, but historically, it's been linked to a reduction in grey matter volume, the type of brain tissue that contains the main body of neurons.

This is a typical pattern of the disease that keeps popping up in research, but while the majority of patients in this new study also showed these deficits, a large chunk had surprisingly healthy grey matter levels.

"Numerous other studies have shown that people with schizophrenia have significantly smaller volumes of brain tissue than healthy controls," explains radiologist Christos Davatzikos from the University of Pennsylvania.

"However, for at least a third of patients we looked at, this was not the case at all - their brains were almost completely normal."

The only thing that stood out was an increase in basal ganglia volume, the part of the brain primarily responsible for motor control. Although schizophrenia is a disorder of the mind that interferes with the consistent processing of reality, it can also lead to physical problems like slow movements and tics.

But these brain patterns are not exactly in line with the current consensus on schizophrenia. In fact, the idea of 'neuroanatomical heterogeneity' - where some people may show brain deficits while others don't - has only recently been considered.

"These results challenge the conventional notion that brain volume loss is a general feature of schizophrenia," the authors conclude.

Using machine learning, the team analysed the brain scans of 307 schizophrenia patients and 364 healthy controls, categorising them into neuroanatomical subtypes.

In total, nearly 40 percent of the participants with schizophrenia did not show the typical pattern of reduced grey matter. In some cases, they actually showed more brain volume in the middle of the brain, in a part called the striatum.

No clear explanation could be found for the results - not medication, age, or any other demographic factors.

"This is where we are puzzled right now," Davatzikos says.

"We don't know. What we do know is that studies that are putting all schizophrenia patients in one group, when seeking associations with response to treatment or clinical measures, might not be using the best approach."

Patients that fell into either brain subtype had experienced similar levels of symptoms and were medicated at roughly the same dose. Previous research has linked reduced cortical volumes to antipsychotic drugs, but the researchers did not detect such differences between the two subtypes.

The team notes that brain differences between the subtypes could still be influenced by the consequences of taking medication, for example, higher treatment resistance in subtype 1 compared to subtype 2, whose cortical volumes did not appear to be reduced. But other aspects - such as no difference in symptom severity - don't seem to support this explanation.

A summary of the two schizophrenia subtypes, SCZ 1 and SCZ 2. (Chand et al., Brain, 2020)

A summary of the two schizophrenia subtypes, SCZ 1 and SCZ 2. (Chand et al., Brain, 2020)

Other recent studies have also hinted at a more diverse presentation of schizophrenia in the brain; given how variable symptoms of schizophrenia can be, and how few people respond to treatment, this idea that one size does not fit all is not without merit.

But connecting these symptoms to patterns in the brain has proved extremely difficult, especially since animal models aren't useful in a disorder that is largely diagnosed through self-reporting.

"The main message is that the biological underpinnings of schizophrenia - and actually many other neuropsychiatric disorders - are quite heterogeneous," Davatzikos told ScienceAlert.

The latest classification of schizophrenia in the DSM-V categorises the condition as a spectrum based on symptoms alone, having moved away from behavioural subtypes such as paranoid and catatonic.

But Davatzikos thinks that observations of neural diversity in such disorders could ultimately take diagnostic categories much further.

"In the future, we're not going to be saying, 'This patient has schizophrenia,' We're going to be saying, 'This patient has this subtype' or 'this abnormal pattern,' rather than having a wide umbrella under which everyone is categorised."

We'll have to wait for even more research in the neuroanatomy of various disorders to see whether such a categorisation goal is attainable.

The study was published in Brain.