An unprecedented glimpse of the human brain as it leaves the womb and enters the outside world has revealed an explosive growth spurt.

Within the first few months of a newborn's life, brain scans suggest, a sudden influx of sensory information triggers the formation of billions of new neural connections that did not exist in the womb.

Previous studies have analyzed fetuses and newborns separately, but this new study considered the brains of 140 individuals on both sides of the birth transition. The dataset includes 126 prenatal scans, starting roughly 6 months post-conception, and 58 postnatal scans, in the three or so months after birth.

"With this one-of-the-kind longitudinal dataset, we now, for the first time, have an opportunity to investigate brain changes across birth," neuroscientist Lanxin Ji from New York University (NYU) told ScienceAlert.

"Surprisingly, there is still a major gap in our understanding of how the human brain changes during this crucial developmental phase."

Principal investigator Moriah Thomason from NYU is a world leader in fetal MRI research, and she has been scanning the brains of mothers and their children for years now. Fetal MRI studies are subject to distortion and signal loss, and because researchers are measuring blood oxygen levels in the brain, this may not be a perfect picture of all the communicating neurons present.

That said, this is the first sizable study to look at how resting functional MRI activity might shift across the birth transition.

"Our results suggest that birth is not merely a continuation of prenatal brain growth but a distinct, transformative stage that impacts future cognitive and behavioral outcomes," explained Ji.

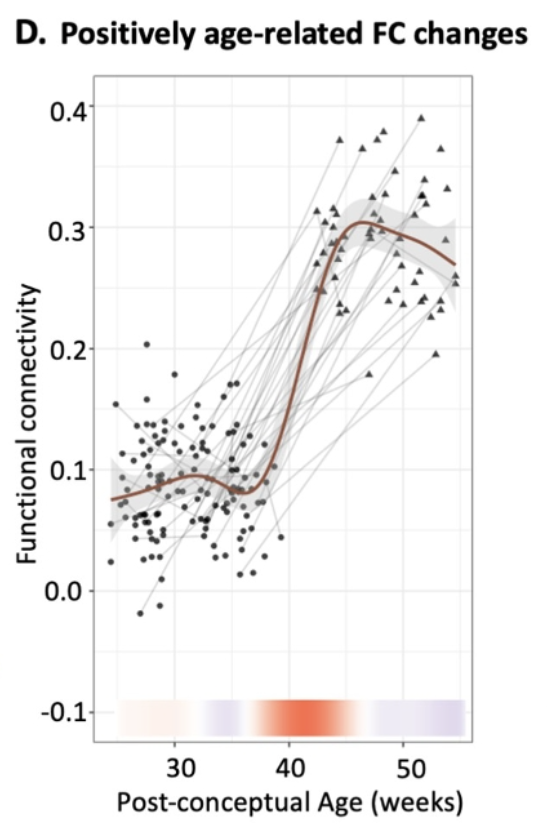

In the weeks following birth, models show a surge in neural connections that suggest the brain is desperately trying to process and integrate new kinds of information.

But not all regions are impacted the same. After leaving the womb, some brain networks blossom with particular complexity, creating lots of new neural connections.

That's especially true in primitive subcortical regions, which are part of a central hub involved in basic life functions like motor control, breathing, blinking, flinching, and digestion.

Parts of the frontal lobe also show dramatic growth spurts after birth, as do several neural bridges connecting regions on either side of the brain, like the bilateral sensorimotor regions, which integrate sensory information to inform motor control.

The new findings support the hypothesis that in the womb, the human brain possesses basic neural networks, which busy themselves with 'local' matters. Upon birth, however, these local affairs go 'global', communicating with networks further away than ever before.

After this initial surge in growth, the newborn brain gradually undergoes reorganization, to prune back inefficient pathways between networks and strengthen others. The result is a massive change in how the brain is wired.

Birth is one of the most significant events in human life, and as advancements in neuroimaging continue, scientists are getting closer to watching that moment unfold in a most crucial organ.

"This work lays the foundation for future work regarding the maturational timing of brain functional networks spanning the perinatal period," Ji told ScienceAlert.

"Extending from this work, one can imagine further studies examining how factors such as sex, prematurity, and prenatal adversity interact with the timing and growth patterns of children's brain network development."

The study was published in PLOS Biology.