A recently developed cancer vaccine for dogs is showing promising results in clinical trials, which have been running since 2016, and there's hope that some of the benefits of the vaccine could be translated into human cancer treatments.

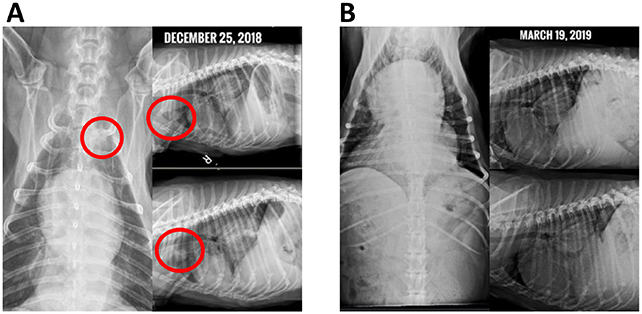

More than 300 dogs have been treated with the vaccine to date, and the twelve--month survival rate for canines with certain cancers has been lifted from about 35 percent to 60 percent. Tumors in many of the animals have also shrunk.

Known officially as the Canine EGFR/HER2 Peptide Cancer Immunotherapeutic, the treatment grew out of studies of autoimmune diseases, where the immune system damages the body's own tissue rather than any invading threats. The vaccine is designed to get the immune system to attack cancer instead.

"In many ways tumors are like the targets of autoimmune diseases," says rheumatologist Mark Mamula, from the Yale University School of Medicine.

"Cancer cells are your own tissue and are attacked by the immune system. The difference is we want the immune system to attack a tumor."

As outlined in a 2021 study by Mamula and colleagues, the treatment gets the immune cells to produce antibody defenses, which attach themselves to tumors and interfere with their growth patterns.

Specifically, these antibodies hunt down two proteins: epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2). Mutations causing overexpression of these proteins drive uncontrolled cell division in some human and canine cancers.

Existing treatments targeting EGFR and HER2 call upon just one kind of antibody. The new vaccine boosts its effects by creating a polyclonal response – one that involves antibodies from multiple immune cells, rather than a single one, making it harder for the cancer to become resistant to the drug.

"In veterinary oncology, our toolbox is much smaller than that of human oncology," says veterinary oncologist Gerry Post, from the Yale School of Medicine. "This vaccine is truly revolutionary. I couldn't be more excited to be a veterinary oncologist."

For now, the vaccine remains a post-diagnosis treatment option rather than any preventative measure, but it's already helped dogs like Hunter: he's now cancer-free, two years after being diagnosed with osteosarcoma, a type of bone cancer.

Typically, only about 30 percent of dogs with osteosarcoma will survive beyond twelve months. Around one in four dogs will get cancer during their lifetimes, so the potential impact of the treatment is huge.

Considering the similarities between dog cancer and human cancer, from genetic mutations and tumor behavior to treatment responses, the researchers suggest the vaccine will also help our understanding of cancers in humans.

The Yale University team isn't the only ones making progress with canine cancer treatments, either. Researchers are also trialing various immunotherapies for dogs with melanoma and lymphoma. However, as with human cancers, not all dogs respond to treatment, and it's difficult to predict which ones do.

"Dogs, just like humans, get cancer spontaneously," says Mamula. "They grow and metastasize and mutate, just like human cancers do."

"If we can provide some benefit, some relief – a pain-free life – that is the best outcome that we could ever have."

The research has been published in Translational Oncology.