New archaeological evidence has allowed scientists to refine the timeline for the Viking presence in North America.

Pieces of wood scarred with cut marks have been precisely dated to the year 1021 CE – exactly 1,000 years ago – and the metal tools that made those marks were not produced by the indigenous population, according to a team of archaeologists led by the University of Groningen in the Netherlands.

Vikings, however, did make and use metal tools, and were known to have settled at the archaeological site of L'Anse aux Meadows, where the wood was found.

This is the earliest and most accurate date yet not just for the European settlement of the Americas, but for circumnavigation of the globe, the researchers said, giving us a definitive reference point for understanding the global transference of knowledge, goods, and genetic information.

It's been known for some time that Vikings traveled to and settled in North America at L'Anse aux Meadows in Newfoundland, Canada long before Christopher Columbus got his sticky paws everywhere. However, a precise date for the brief occupation has been difficult to obtain.

In recent years, however, archaeologists have been making more and more use of an incredible and creative dating tool: dendrochronology, based on counting tree rings.

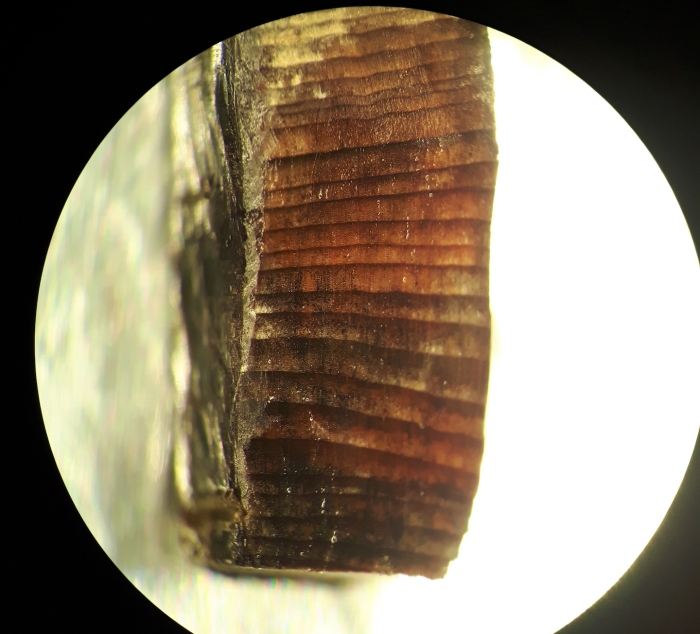

Microscopic detail of tree rings on a L'Anse aux Meadows wood fragment. (Petra Doeve)

Microscopic detail of tree rings on a L'Anse aux Meadows wood fragment. (Petra Doeve)

You might think that would be rather difficult for a piece of chopped wood of unknown age, but help comes from an unexpected place: solar storms.

The evidence can be found in abundances of a radioactive isotope of carbon called carbon-14, or radiocarbon. Radiocarbon only occurs on Earth in trace amounts compared to the other naturally occurring carbon isotopes.

It's formed in the upper atmosphere under the bombardment of cosmic rays from space. When cosmic rays enter the atmosphere, they interact with the local nitrogen atoms to trigger a nuclear reaction that produces radiocarbon. Since cosmic rays are constantly streaming through space, Earth receives a more or less steady supply of radiocarbon.

Some of this can be found, naturally, in tree rings. And every now and again, a large radiocarbon spike turns up in tree rings, fading over several years. Since a rather significant known source of cosmic rays is solar activity, these spikes are usually interpreted as evidence of solar flares and storms.

Just such a solar storm has been identified in tree rings from around the world, dated to 992 to 993 CE based on the rate of radioactive decay of radiocarbon. This spike also appears in four pieces of cut wood found at L'Anse aux Meadows, the researchers found.

"Finding the signal from the solar storm … [in] the bark allowed us to conclude that the cutting activity took place in the year 1021 CE," said archaeologist Margot Kuitems of the University of Groningen.

Other researchers have used dendrochronology to help piece together a history of solar activity and ancient supernovae. This finding adds another feather to the cap of dendrochronology, demonstrating that solar storms can be used as a reliable and precise reference point for contextualizing archaeological artifacts, too.

"We provide evidence that the Norse were active on the North American continent in the year AD 1021," the researchers write in their paper.

"This date offers a secure juncture for late Viking chronology. More importantly, it acts as a new point-of-reference for European cognizance of the Americas, and the earliest known year by which human migration had encircled the planet."

The research has been published in Nature.