Phase 1 clinical trials are showing promising signs for a new drug that successfully reduced weight and fat mass in obese mice on a high-fat diet while not disrupting their appetite.

If human trials are successful, the drug could revolutionize treatment for people with obesity, enabling weight loss that doesn't involve losing appetite or avoiding fats.

The drug targets an enzyme found in brain cells called astrocytes, which can regulate body weight by acting on a distinct group of neurons, according to new research led by the Institute for Basic Science (IBS) in Korea.

"Previous obesity treatments targeting the hypothalamus mainly focused on neuronal mechanisms related to appetite regulation," says IBS neuroscientist Moonsun Sa, first author of the study.

"To overcome this, we focused on the non-neuronal 'astrocytes' and identified that reactive astrocytes are the cause of obesity."

Our brain's hypothalamus controls the delicate balance between eating and burning calories, and we know that neurons in the area connect to fat tissue and regulate fat metabolism, but exactly how has been hazy.

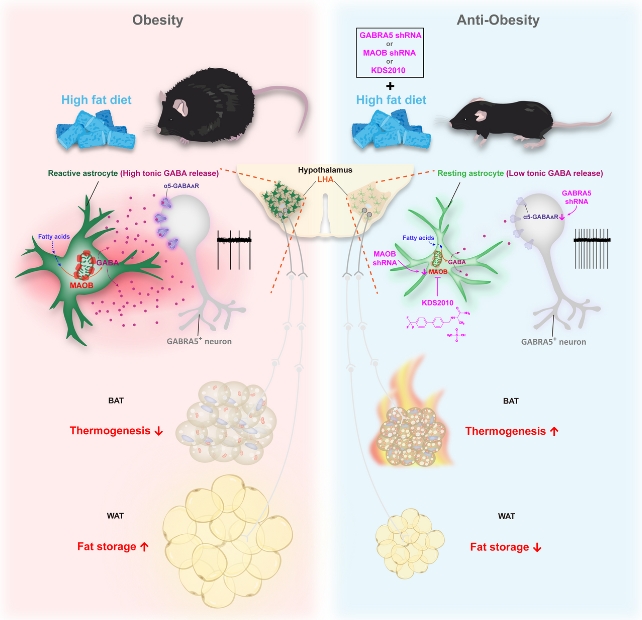

In a mouse model of obesity induced by a high-fat diet, the researchers found that activity was significantly reduced in a group called GABRA5 neurons.

So they experimented with decreasing GABRA5 neuron activity in control mice using chemicals. This led to weight gain via reduced heat production (thermogenesis) in brown fat and greater white fat storage.

On the other hand, stimulating GABRA5 neurons in the hypothalamus led to significant weight loss in obese mice, indicating GABRA5 neurons can function like a reversible toggle to control weight.

"We have discovered the existence of a unique population of fat-burning neurons," the authors write in their published paper.

Sa and colleagues were surprised to find that astrocytes were controlling the activity of this group of GABRA5 neurons switching weight loss on and off. Astrocytes react to disease and injury by releasing chemicals to help protect neurons from damage.

They discovered that reactive astrocytes are more common in the brains of mice with obesity compared to those with healthy weights.

These reactive astrocytes express more of an enzyme called MAOB, which produces an inhibitory neurotransmitter called GABA. The increase in GABA is what causes the GABRA5 neurons to slow down and stop working properly, leading to weight gain.

So the team thought that if increasing the activity of GABRA5 neurons reduces fat storage, then blocking astrocytes from producing GABA is a potential molecular target for treating obesity.

That's where the promising new drug comes in. Called KDS2010, it inhibits the MAOB enzyme in reactive astrocytes, thereby blocking production of GABA and allowing GABRA5 neurons to function normally and promote weight loss.

KDS2010 treatment yielded remarkable results in obese mice. Their fat tissue metabolism increased, fat storage decreased, and they lost weight despite being fed a high-fat diet, without impacting the amount of food they ate.

This study tested male mice only, so there may be more to learn in further research. We might know more soon enough, as a biotech company called Neurobiogen – which is affiliated with the research team – is currently undertaking Phase 1 clinical trials with KDS2010.

"Obesity has been designated by the World Health Organization (WHO) as the '21st-century emerging infectious disease,'" IBS neuroscientist C. Justin Lee says.

"We look to KDS2010 as a potential next-generation obesity treatment that can effectively combat obesity without suppressing appetite."

The study has been published in Nature Metabolism.