For the first time, scientists have managed to genetically modify stem cells inside the bodies of mice, a feat which could eventually open up new potential in stem cell therapy.

Stem cells can develop into all kinds of other cells, and the body uses these diverse tools for both growth and repair. Because of their remarkable abilities, there's interest in using stem cells for certain medical treatments, but that road is not always easy.

For example, in one particular type of bone marrow transplant, the stem cells that produce blood have to be removed from the body and genetically modified before being transfused back into the patient.

The results of this new study in mice indicate we might be able to remove the risky and complicated extraction step: the necessary genetic edits could be made in vivo, which is likely to be both faster and more effective than the techniques used today.

"When you take stem cells out of the body, you take them out of the very complex environment that nourishes and sustains them, and they kind of go into shock," says the senior researcher behind the study, Amy Wagers from Harvard University in Massachusetts.

"Isolating cells changes them. Transplanting cells changes them. Making genetic changes without having to do that would preserve the regulatory interactions of the cells – that's what we wanted to do."

And the researchers did it by using what's known as an adeno-associated virus (AAV) – a virus that's able to go into the body to infect and alter the cells of humans (or, in this case, mice) without actually causing disease.

In tests on mice, AAVs packing CRISPR gene-editing technology were delivered to different types of skin, blood, and muscle stem cells, and progenitor cells (similar to stem cells but more specific and developed).

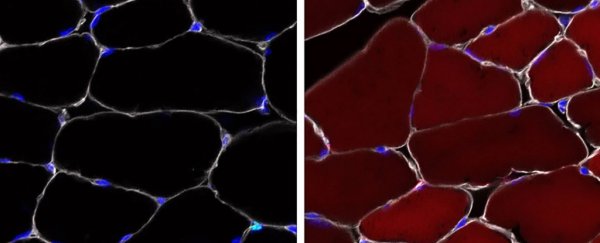

Thanks to the use of activated 'reporter' genes which glow a fluorescent red colour inside the cells, the researchers were able to observe the genetic changes: up to 60 percent of the stem cells in skeletal muscle, up to 38 percent of the stem cells in bone marrow, and up to 27 percent of skin progenitor cells.

Those numbers might not seem all that high but they're a very good start, and the scientists found evidence of the changes applied by the stem cells spreading through the bodies of the animals.

"So far, the concept of delivering healthy genes to stem cells using AAV hasn't been practical because these cells divide so quickly in living systems – so the delivered genes will be diluted from the cells rapidly," says one of the team, Sharif Tabebordbar from the Broad Institute in Massachusetts.

"Our study demonstrates that we can permanently modify the genome of stem cells, and therefore their progenies, in their normal anatomical niche. There is a lot of potential to take this approach forward and develop more durable therapies for different forms of genetic diseases."

There's plenty of work to do yet, not least demonstrating that the same techniques can work in humans as well as mice, but this new study shows that the AAV and CRISPR approach is one of the most promising we have.

As well as giving us more effective stem cell tools for tackling diseases at their very core, the research also opens up different options for studying genetically edited stem cells in their natural habitat rather than the lab.

"The approach we developed gets around all the problems you introduce by taking stem cells out of a body and allows you to correct a genome permanently," says Wagers.

"AAVs are already being used in the clinic for gene therapy, so things might start to move very quickly in this area."

The research has been published in Cell Reports.