When people with metastatic breast cancer close their eyes at night, their cancer awakes and starts to spread.

That's the striking finding from a paper published in Nature this week that overturns the assumption that breast cancer metastasis happens at the same rate around the clock.

The result may change the way that doctors collect blood samples from people with cancer in the future, the researchers say.

"In our view, these findings may indicate the need for healthcare professionals to systematically record the time at which they perform biopsies," says senior author Nicola Aceto, a professor of molecular oncology at ETH Zurich.

"It may help to make the data truly comparable."

Researchers first stumbled across this topic when they noticed an unexplained difference in the number of circulating tumor cells in samples analyzed at different times of the day.

"Some of my colleagues work early in the morning or late in the evening; sometimes they'll also analyze blood at unusual hours," Aceto says.

Mice that seemed to have a much higher number of circulating cancer cells than humans provided another clue: Mice sleep during the day when blood samples are most often taken.

To investigate what was going on, the Swiss researchers studied 30 women with breast cancer (21 patients with early breast cancer that had not metastasized and nine patients with stage IV metastatic disease).

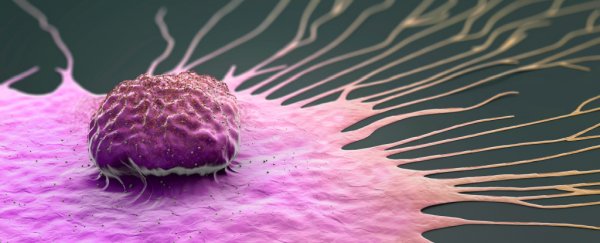

They found "a striking and unexpected pattern": Most circulating tumor cells (78.3 percent) were found in blood samples that were taken at nighttime while a much lower amount was found in daytime samples.

When the researchers injected mice with breast cancer cells and took blood samples during the day, they found the same result. Circulating tumor cells were much higher when the mouse was at rest.

Interestingly, the cancer cells collected during the rest period were "highly prone to metastasize, whereas circulating tumor cells generated during the active phase are devoid of metastatic ability", the researchers said.

Genetic analysis revealed that tumor cells taken from mice and humans at rest had upregulated their expression of mitotic genes. This makes them better at metastasizing as mitotic genes control cell division.

The researchers ran experiments where they gave some mice jet lag by changing the light-dark routine. Messing with the circadian rhythm led to a massive decrease in the concentration of circulating tumor cells in mice.

In another experiment, the researchers tested whether giving the mice hormones that were similar to those found in the body when mice are awake would affect the number of circulating tumor cells when the mouse was at rest.

They injected mice with testosterone, insulin (a hormone that makes it possible to turn sugar into energy), and dexamethasone (a synthetic chemical that acts like cortisol, the stress hormone).

The researchers found a "marked reduction" in the number of circulating tumor cells in a blood sample taken during the rest period (when the tumor would normally be most aggressive).

"Our research shows that the escape of circulating cancer cells from the original tumor is controlled by hormones such as melatonin, which determine our rhythms of day and night," says Zoi Diamantopoulou, the study's first author and a molecular oncology researcher at ETH Zurich.

This paper was published in Nature.