The intricate details of tattoos inscribed on the skin of South American mummies are now revealed in all their breathtaking glory.

With a technique used to study dinosaur fossils, a team of scientists has revealed the fine work that went into creating the elaborate tattoos found on the mummies of individuals from the Chancay culture that lived in Peru some 1,200 years ago.

"Laser-stimulated fluorescence lets us see tattoos in their full glory, erasing centuries of degradation," says paleontologist Thomas Kaye of the Foundation for Scientific Advancement in the US.

"The Chancay culture, known for its mass-produced textiles, also invested significant effort in personal body art. This could point to tattoos as a second major artistic focus, perhaps carrying deep cultural or spiritual significance."

Humans have been adorning our bodies with permanent tattoos for thousands of years. Our oldest evidence for the practice dates back more than 5,000 years in multiple parts of the world, but it's not easy to find, because soft tissue decomposes so quickly.

In the cases where the skin is preserved – usually mummification – any extant tattoos can become hard to see as the skin darkens and turns leathery, and ink lightens and bleeds into surrounding tissue.

This is where Kaye and his colleague, paleobiologist Michael Pittman of the Chinese University of Hong Kong, enter the picture. For the last decade, the pair has been using laser-stimulated fluorescence (LSF) to reveal hidden details in the soft tissue of dinosaurs.

"Two years ago Judyta Bąk, a PhD student of a colleague at Institute of Archaeology at Jagiellonian University in Kraków, Poland, reached out to ask if our technology could be used to improve study of tattoos from mummified human remains," Pittman told ScienceAlert.

"We told her that we would expect our imaging to work and that it would probably work better since more of the original chemistry would be preserved compared to fossilised remains. Within a few months we were on a plane to Peru to collect data from all over the country. We found our most spectacular results from tattoos of the Chancay culture."

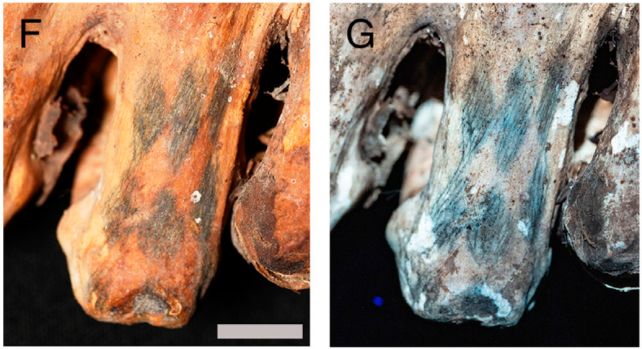

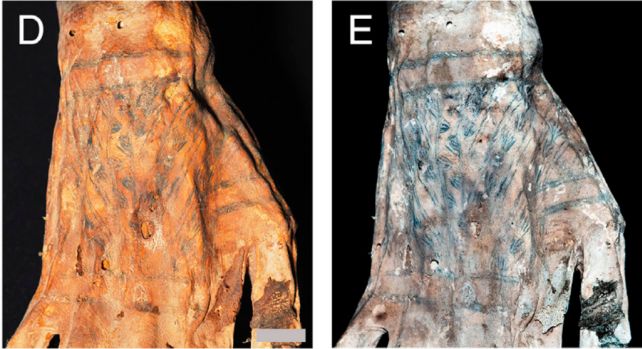

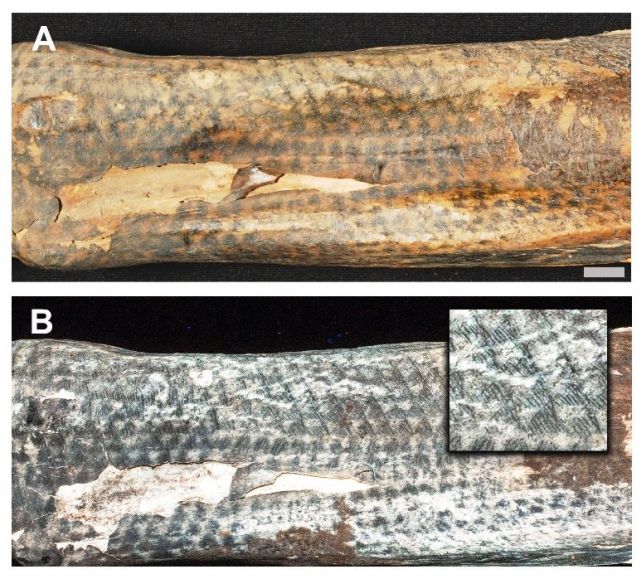

It's the first time this technique has been used to study tattooed mummies, and the results are nothing short of spectacular. The researchers examined more than 100 individuals. Not all the individuals turned out to have tattoos, but for those that did, their skins fluoresced brightly under laser stimulation, while the tattooed areas did not.

This generated high-contrast images that all but eliminated the effects of ink bleed, revealing tattoos so finely inscribed, the method of their creation is difficult to determine.

However, lines with widths between 0.1 to 0.2 millimeters suggests single-needle puncture tattooing, as opposed to making incisions and rubbing them with dye, as has previously been suggested for ancient tattoos.

This is also consistent with a recent experimental study that found the 5,300-year-old tattoos on Ötzi the Iceman were created using puncture tattooing.

"We still don't know exactly how the tattoos were made, but it involved a point finer than a modern #12 tattoo needle (0.1 - 0.2 mm compared to 0.35 mm)," Pittman said.

"This suggests a traditional needle-based tattooing technique, as opposed to 'cutting and filling'. Based on what was available to the Chancay, the tattoos were probably made with a cactus needle or a sharpened animal bone."

Although we won't know for sure unless some ancient tattooing tools are recovered, we can make some other inferences about the Chancay culture based on the level of detail in their tattoos. They would have taken some time and effort to accomplish, which implies that they carried strong significance to the people who made and bore them.

The researchers were also able to compare the tattoos to patterns on the textiles and pottery for which the Chancay people are known. The intricacy of the tattooed designs was comparable to these other art forms, suggesting that tattoos were an important part of the aesthetic lives of the Chancay.

There was also some variability in the intricacy and quality of the tattoos, which could mean varying skill levels among the artists who created them. To compare it to tattoo artists today, some marks may have been made by apprentice-level tattooists, while the more intricate designs could have been made by artists with years or decades of experience.

And those ancient, long-dead masters may even be able to inform our own techniques, centuries after they lived.

"I still can't believe how narrow the lines were in the high-detail tattoos we studied," Pittman said. "The fact that a standard #12 modern tattoo needle can't do this tells us there is still a lot to learn from early tattoo making even from tattoos that are over 1,000 years old."

It's new ground in the study of ancient tattooing practices and techniques, and now the team are keen to explore further. They plan to extend their work to mummies from around the world, to help shed some light on the different ways and reasons our ancestors marked their bodies.

"Tattoos can hold so much information including about culture and what is important to the individual with the tattoos," Pittman explained.

"Studying early tattoos provides rare windows to these aspects sometimes in ways that are not available from other archaeological evidence, as our high-detail tattoo discovery shows."

The research has been published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.