Ordnance Survey, the official British mapping agency, has made its first ever map of another planet, using NASA data to chart a huge expanse of the surface of Mars.

The organisation, which turns 225 years old this year, made the map as an experiment to see if its techniques could be of potential use for future missions to the red planet. Now complete, the map covers 3,672 x 2,721 kilometres (2,281 x 1,690 miles) at a scale of 1 to 4 million, and could be used to help explain future Mars missions for the benefit of public.

"Becoming more familiar with space is something that interests us all and the opportunity to apply our innovative cartography and mapping tradecraft to a different planet was something we couldn't resist," said Ordnance Survey's (OS) director of products, David Henderson.

"We were asked to map an area of Mars in an OS style because our maps are easy to understand and present a compelling visualisation, and because of this we can envisage their usefulness in planning missions and for presenting information about missions to the public."

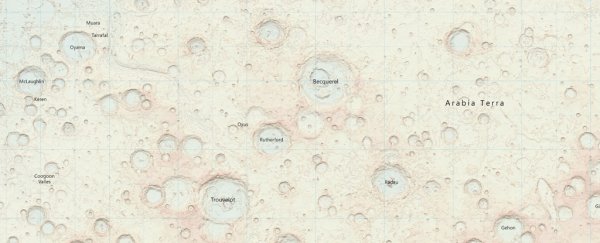

Available online – at a hefty 70MB in its original resolution – and in a one-off paper edition for would-be Mars tourists who need a foldable copy at hand, the map shows an area of Mars called the Western Arabia Terra.

Ordnance Survey

Ordnance Survey

This region encompasses the landing sites of both the Mars Pathfinder (in northwest Ares Vallis) and the Opportunity rover (east of Margaritifer Terra).

Chris Wesson, OS's cartographic design consultant, designed the map over a couple of months, with a focus on delivering a style that would be easy for anybody to understand, whereas most planetary maps are designed with a purely scientific audience in mind.

"We have set out from the start to treat the Mars data no different to how we would treat [standard British mapping] data or any other Earth-based geography," he said. "The key ingredients to this style are the soft colour palette of the base combined with the traditional map features such as contours and grid lines, and the map sheet layout complete with legend."

That palette involved discounting red, despite Mars's affiliations with the colour. Wesson describes red as being a "very dominant" colour that would clash with overlays and text elsewhere on the map. As he points out, Earth's maps aren't always green and blue either, but are designed primarily with legibility in mind.

The biggest challenge involved finding a way of conveying varying height information for a planet that exhibits a dramatic range of peaks and falls.

"Mars is a very different topography to Earth to map," said Wesson. "The surface is very bumpy but at such a large scale I had vast expanses of land that appeared flat relative to the craters each of several thousands of metres depth, hence the need for different lighting and surface exaggerations. This varying topography led to several attempts by trial and error to find a workable contour interval."

As to whether tourists to Mars might one day use his map to help get around the place, Wesson isn't so sure. "It is a nice thought, that one day people could pinpoint the landscape around them from a map just as in the British countryside, but the map may be quite different by then," he said.