Recorded on the bones of a woman who lived more than 2,000 years ago in Dorset is a life marred by tragedy and pain.

The evidence shows that she lived a physically demanding life, before it was cut prematurely short in her late 20s – and that her death was a brutal one. Her rib was fractured just a few weeks prior to her death; and a cut mark on her neck suggests that her death was violent and bloody. And her burial was highly unusual.

Archaeologists led by Miles Russell of Bournemouth University in the UK believe this constitutes rare but convincing evidence the woman was a human sacrifice.

"In the other burials we have found, the deceased people appear to have been carefully positioned in the pit and treated with respect, but this poor woman hasn't," says forensic anthropologist Martin Smith of Bournemouth University.

"We have also previously found ceramic pots and remains of joints of meat next to human remains, which we believe are offerings for the afterlife. This was nothing like that. The young woman was found lying face down on top of a strange, deliberately constructed crescent shaped arrangement of animal bone at the bottom of a pit, so it looks like she was killed as part of an offering."

The fully articulated skeleton was uncovered during an archaeological dig in the south of the UK back in 2010, and the strangeness of the burial immediately stood out. But to learn the story of the woman who lived and died around 350 BCE, so many years ago, a detailed study of the bones was required.

The researchers performed osteological analysis and scanning electron microscopy of the bones, isotope analysis on one of her teeth, and a three-dimensional reconstruction of the body and the marks thereon. They also studied the animal remains that appeared to be included in the woman's burial.

The results were sobering. Her spine showed signs of degeneration and damage, and her bones had well-developed, robust muscle attachments. These are both signs of hard labor, over a long period of time.

Isotope analysis is a technique that identifies ratios of isotopes that replace calcium in a living creature's teeth and bones. These isotopes come from the food eaten over the course of a lifetime; and, since different ratios and different isotopes are present in different foods and locations, they can be used to track where a person or animal has traveled and what they ate.

Strontium isotope ratios in the woman's teeth revealed that she may not have been born in the village where she died and was buried, but likely came from the south of England or possibly elsewhere in Europe.

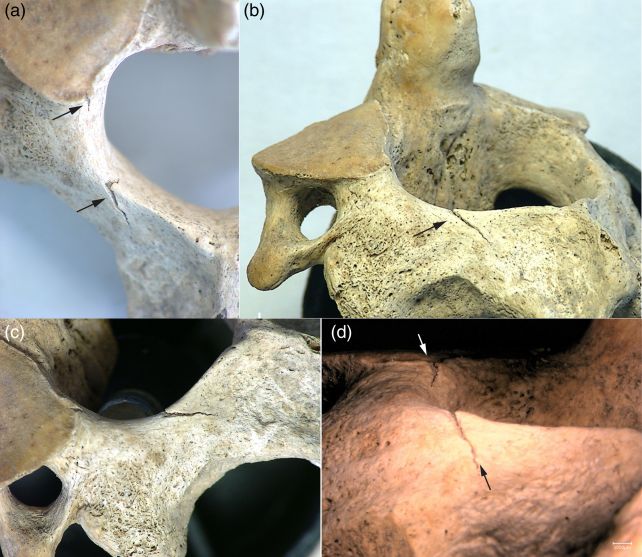

And, finally, there are her injuries. One of her ribs had a fracture that had partially healed, which means she lived for a short time after sustaining it. And the cut mark on her cervical vertebra – her neck – had no signs of healing. It's likely the wound that killed her.

Her burial arrangement, too, is odd. She was found face-down in the bottom of a storage pit, in an attitude that suggests that this is where she was killed and left. However, the animal bones around and under her – mainly horse and cow bones – seem to have been deliberately arranged, rather than dumped as waste.

Human sacrifice in the British Iron Age has been mentioned by a number of authors throughout the millennia, but actual physical evidence of it is scant. This, the researchers say, could be an example of one such ritual murder.

"All the significant facts we have found such as the problems with her spine, her tough working life, the major injury to her rib, the fact she could have come from elsewhere, and the way she was buried could be explained away in isolation," Smith says.

"But when you put them all together with her deposition face down on a platform of animal bone, the most plausible conclusion is that she has been the victim of a ritual killing. And of course, we found a large cut mark on her neck, which could be the smoking gun."

Generally, the burials that get the most archaeological attention are those of high-status individuals. This is a rare, sad exception, the community-sanctioned killing of a low-status, marginalized individual whose bones reveal the darkness on the other side.

"Behind every ancient burial we find," Smith says, "is someone's story waiting to be told."

The research has been published in the Antiquities Journal.