A survey carried out of the Baltinglass landscape in Ireland has uncovered the first cluster of rare and mysterious Neolithic cursus monuments to be found in the country.

Common throughout the British Isles, only around 20 of these extremely elongated, narrow trenches had been found in Ireland before this latest discovery. Even then, they were only ever uncovered on their own or in pairs.

Now, five cursus monuments have been found together, potentially giving experts new insight into what exactly they were used for.

The name 'cursus' is a hangover from early speculations that the depressions may have been 'courses' left by Roman chariots. As more of the structures have been uncovered over recently centuries, typically near other great monuments like Stonehenge, the reasons for their construction have only become more mysterious.

Most were dug between 4000 and 2400 BCE. Excavated into the earth with few internal features, some had wooden posts added shortly or some time after. That's not a whole lot for archeologists to go on.

Archaeologist James O'Driscoll from the University of Aberdeen in the UK carried out a survey of the Baltinglass area, using LIDAR to bounce laser pulses off the landscape and uncover shapes and patterns that had otherwise been obscured by many millennia of weathering and agricultural use.

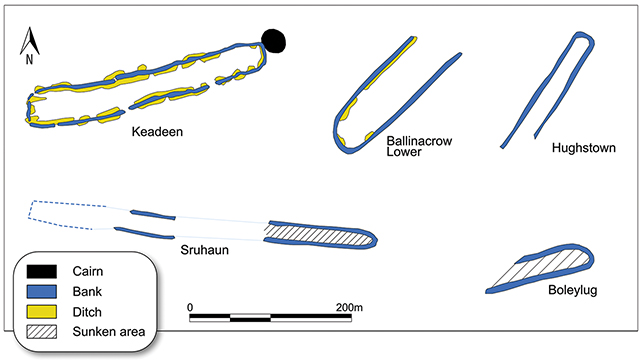

Five of those shapes appear to be cursus monuments, the first to be discovered here – though the region is already well known for its archaeological significance. The longest is 427 meters (1,401 feet) in length.

"Their unique morphology, location, and orientation offer insights into the ritual and ceremonial aspects of the farming communities that inhabited the Baltinglass landscape and hint at the variability in the form and possible functions of these monuments for early farming communities," writes archaeologist James O'Driscoll, from the University of Aberdeen in the UK, in his published paper.

While O'Driscoll acknowledges there isn't much hard evidence for how these cursus monuments were used, there are some clues: their location in relation to known burial sites, their orientation in terms of the path of the Sun, and their alignment in the context of hills and valleys.

As noted in previous research, those clues suggest these pathways may have been used to transport the dead to their final resting place, accompanied by a funeral procession. In certain cases here, the cemetery sites wouldn't have been visible until the procession reached the end of the cursus, which was perhaps intentional.

"The cursus may have directed the traveler towards their final resting place in a burial monument, which, at Baltinglass, lay deliberately just out of sight of the living processing within or alongside the cursus," writes O'Driscoll.

At the start of the western European Neolithic era (around 7000 BCE), communal structures first started appearing, drawing together groups of people that had previously been scattered. These larger complexes, including the cursus monuments, were built using a lot of time, work, and materials that would have exceeded the resources of one community alone.

"Further analysis of the Baltinglass cursus monuments, as well as Irish examples more broadly, holds great potential for understanding Middle Neolithic ritual and ceremonial practices," writes O'Driscoll.

The research has been published in Antiquity.