In recent years, evidence suggests that there might be something lurking on the outskirts of the Solar System – something large, and possibly very dark.

That large, dark thing has been named Planet Nine, its presence inferred by some peculiarly clustered orbits detected in small objects in the outer Solar System's Kuiper Belt. Something, some scientists believe, has caused a gravitational disruption that created these orbits.

Their calculations suggest that, whatever it is, the object is between 5 and 10 times the mass of Earth.

However, the outer Solar System is very far away, and objects in it are very hard to detect. Planet Nine, if it exists, should be orbiting the Sun somewhere between 400 and 800 times the distance of Earth from the Sun. So, although scientists have been searching for Planet Nine, so far, it's eluded everyone.

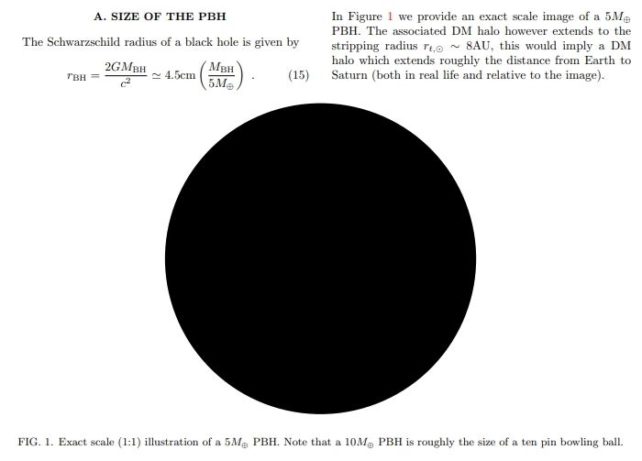

One possible reason for this could be if Planet Nine is a dark object; like, for example, a black hole. Not only would such a black hole not emit any light, it would be extremely small – practically impossible to spot even if it could reflect light.

But astronomer Man Ho Chan of The Education University of Hong Kong in China believes that we might still be able to locate it anyway.

The smoking gun, he lays out in a paper uploaded to preprint server arXiv, and in press at The Astrophysical Journal, could be a bevy of moons attendant on the mysterious chunk of something.

"In this article, we show that the probability of capturing large trans-Neptunian objects (TNOs) by Planet Nine to form a satellite system in the scattered disk region (between the inner Oort Cloud and Kuiper Belt) is large," Chan writes in his paper.

"By adopting a benchmark model of Planet Nine, we show that the tidal effect can heat up the satellites significantly, which can give sufficient thermal radio flux for observations, even if Planet Nine is a dark object."

Almost every planet in the Solar System has at least one moon. In fact, most have more than one. Mercury and Venus are moon-free, and Earth is the only planet with just one satellite. Some non-planetary bodies have moons, too. There's Pluto, of course, with its moons. Some asteroids even have moons.

In the mid to outer Solar System, moons are pretty much all the rage. Some, like Earth's Moon, could have been formed from material from the parent body itself. In many other cases, the planet's gravity snared passing rocks and kept them, like weird little rock-collecting goblins.

Where Planet Nine is predicted to be, as it turns out, should be ripe for the moon-picking: the region between the rock-filled Kuiper Belt and the rock-filled Oort Cloud. This region, known as the scattered disk, should be filled with trans-Neptunian objects; basically, rocks that have an orbit at a greater average distance than Neptune.

Chan calculated the probability that the putative planet could have picked up some satellites, and found that it would be more peculiar if it hadn't. According to his calculations, on average, an object the mass of Planet Nine should capture 20 trans-Neptunian objects as large as or larger than 140 kilometers (87 miles) across.

On their own, these pieces of icy rock wouldn't be detectable, but a gravitational interaction with a more massive body could change that, if the moon was big enough; say, larger than 100 kilometers across.

Satellites that are captured by a planet tend to have irregular, elliptical orbits. This means that the gravitational stresses placed on the moon change as it moves closer to and farther away from the planet, stretching it out where the gravitational pull is strongest.

These constantly changing stresses heat the moon from the inside. And heat is dissipated as thermal radiation. This should be detectable as a radio signal; and it's something we can look for now, Chan says.

"If P9 is a dark object and it has a satellite system, our proposal can directly observe the potential thermal signals emitted by the satellites now," he writes.

"Therefore, this would be a timely and effective method to confirm the Planet Nine hypothesis and verify whether Planet Nine is a dark object or not."

Well, it's as good a thing to try as any.

The paper is in press with The Astrophysical Journal, and can be accessed on arXiv.