A new study highlights how drinking more than three cups of coffee a day affects dopamine levels in the brains of people with Parkinson's, a finding that potentially influence how we monitor and perhaps one day treat the disease.

The research, led by a team from the University of Turku and Turku University Hospital in Finland, was undertaken to fill in a specific knowledge gap: how coffee consumption affects people already diagnosed with, and showing symptoms of, Parksinon's.

Symptoms of Parkinson's disease arise with the marked loss of dopamine-producing cells in a brain region called the substantia nigra. Previous studies have suggested that drinking coffee can reduce the risk of developing Parkinson's, and that caffeine's effects on receptors in the nigrostriatal

dopamine system could be involved.

"The association between high caffeine consumption and a reduced risk for Parkinson's disease has been observed in epidemiological studies," says neurologist Valtteri Kaasinen, from the University of Turku.

"However, our study is the first to focus on the effects of caffeine on disease progression and symptoms in relation to dopamine function in Parkinson's disease."

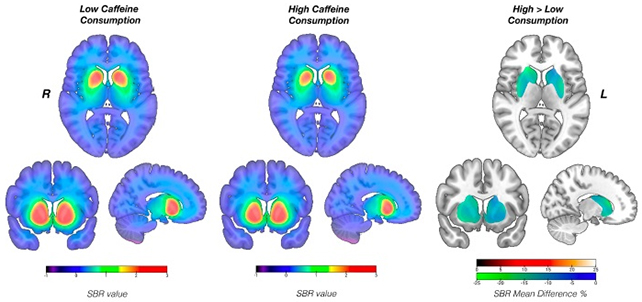

The researchers recruited 163 people with early-stage Parkinson's and 40 healthy controls, with 44 participants with Parkinson's called in for a second assessment that was, on average, six years later. Coffee consumption was compared to to a transporter molecule carrying dopamine in the brain.

In the follow-up assessments, those who typically consumed three or more cups of caffeinated coffee a day (measured through both self-reporting and blood samples) showed 8.3 to 15.4 percent lower dopamine transporter binding than those who drank fewer than three cups, the study found.

That means less dopamine being produced. In spite of links with initial risk reduction, the team found no signs of any restorative function for caffeine in the brains of people with ongoing Parkinson's symptoms. What's more, the researchers didn't observe any improvements in the symptoms of Parkinson's in people who drank more coffee either.

"While caffeine may offer certain benefits in reducing the risk of Parkinson's disease, our study suggests that high caffeine intake has no benefit on the dopamine systems in already diagnosed patients," says Kaasinen.

"A high caffeine intake did not result in reduced symptoms of the disease, such as improved motor function."

The researchers think the downregulation of dopamine seen in the high coffee consumers is the same balancing out effect that happens in the brains of healthy individuals. It's also something that has been seen with other psychostimulant drugs.

Intriguingly, consuming coffee within a close period to clinical dopamine transporter imaging could affect the test's results, potentially adding complications to how they're interpreted.

While there's no dramatic finding here in terms of coffee drinking making a difference in Parkinson's patients, the study does add important new evidence regarding the relationship between dopamine and Parkinson's, getting us closer to a full understanding of the disease and how to combat it.

"Our results do not support advocating caffeine treatment or increased coffee intake for newly diagnosed Parkinson's disease patients," write the researchers.

The research has been published in the Annals of Neurology.