After 700 days of antibiotic treatment, the infection of a 30-year-old bombing attack victim still raged.

Tragically, the patient had suffered life-threatening injuries during the attacks at Brussels airport on 22 March 2016. Over the next three years, she faced numerous medical complications, as her fracture-related wound became infected with pan-drug-resistant bacteria, or what we know colloquially as superbugs.

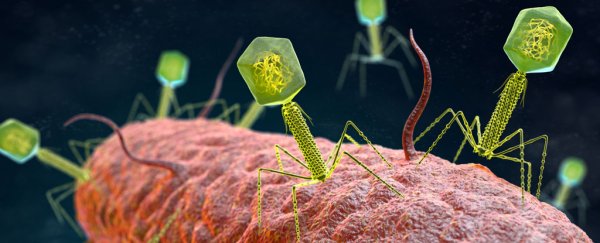

Confronted with little progress, clinicians decided to turn to a combination of antibiotics and specialized bacteriophage therapy, a new treatment that harnesses specialized viruses that infect and kill bacteria. Her unique and successful case has now been described in Nature Communications.

Superbug infections are becoming an increasingly serious health issue, with phage therapy being amongst the most promising new tools in our arsenal.

Normally, phages infect a subset of strains of bacteria that belong to a single bacterial species, however, clinicians have been working on personalized forms of phage therapy, where phages from a prepared bank are selected by analyzing the bacterial strains isolated from the patient's bacterial infection.

When enough time and resources are available, clinicians can select 'preadapted' phage mutants that have an increased capacity for infecting the patient's specific type of bacterium, or that may have a reduced capacity to provoke bacterial resistance. The last decade has seen a surge in this type of phage therapy research.

The clinicians behind this patient's case study explain that most phage treatments developed by western countries are generalized "cocktails" which don't take into account the evolutionary battle between the bacteria and phages that often makes them so specific to each other.

"In recent randomized controlled trials, these static phage cocktails showed disappointing results, which contrast with those of an increasing number of case studies using phages as adjunctive therapy, or preadapted (or even engineered) phages that are more effective against the infecting bacteria," add the authors.

In this particular case, the patient's drug-resistant infection was due to resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae, a particularly nasty superbug that forms persistent biofilms which enable it to bounce back from repeated antibiotic treatments.

"Biofilms are structures elaborated by bacterial communities attached to the surface of implants or avascular tissue fragments. Within biofilms, persistent cells form a subpopulation of metabolically dormant cells that play a major role in the capacity of biofilms to survive and recover from antibiotic treatment," the authors explain.

Currently, there is still a lack of data on the overall effectiveness of phage therapy for resistant bacterial infections, as well as the potential of any adverse effects that may come to patients.

Because of this, the doctors took precautionary steps, applying the phages locally to the infected areas, rather than intravenously. Additionally, a short course of phage treatment – just six days – was chosen to minimize the chance of the patient's immune system responding negatively.

However, three months after the phage treatment, the patient's condition dramatically improved, with the bacterial infection finally beaten.

The authors believe that the combination of a personalized phage treatment, coupled with the use of a longer course of antibiotics afterwards, formed a sort of one-two punch, where phages were able to break down the defensive biofilms, allowing the antibiotics a clear path to finally eliminate the bacterial infection.

"In vitro data indicates that the phage-antibiotic combination was more effective in reducing bacterial counts for K. pneumoniae in mature biofilms than antibiotics or phage alone."

Thankfully, there were no observed negative outcomes associated with the use of phages for the patient. Three months after the initiation of the phage-antibiotic therapy, the woman's condition had drastically improved across the board, and her wound was finally healing properly.

Finally, 798 days post-injury, the clinicians were able to discontinue the antibiotic treatment; there was no sign of recurrent infection afterwards, and the patient has been able to slowly regain mobility.

"The present case study can open a new way of thinking about phage therapy: the use of individually adjusted phage-antibiotic combinations," the authors write.

The study was published in the journal Nature Communications.