Snakes don't bother with chewing - they open wide, swallow prey whole, and digest it at leisure. But the cat-eyed water snake from southeast Asia has figured how to rip its food into pieces - and that's pretty impressive for an animal without any limbs.

Snakes don't have paws to hold their food down, or teeth suited for tearing or chewing, so swallowing food whole makes the most sense.

The small cat-eyed water snake (Gerarda prevostiana) lives in the mangroves, where food isn't always soft and squishy.

But a team of researchers from the University of Cincinnati has discovered this snake not only thrives in its environment, but has even managed to become a picky eater - it likes to feast on crabs, typically known for having spiky, hard shells.

As it turns out, the snakes have found a small window just after a crab has moulted, or shed its hard exoskeleton as it grows. At this point, the crustacean is much softer than usual, while its new shell hardens within less than an hour - and this is when the water snake strikes.

"The snakes only have about a 20-minute window to eat the crab the way they really like them," explained lead author Bruce Jayne, a biologist at the university.

Because the moulting crabs are soft, it's easy for the snakes to rip them into smaller chunks. And yeah, they can totally do that without hands.

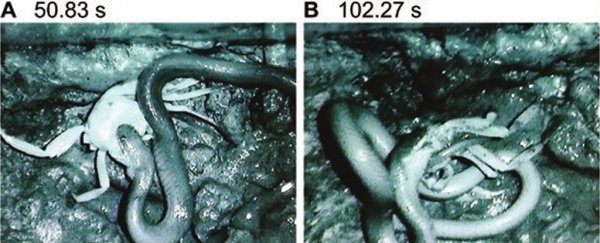

The snake grasps the crab with its mouth, then forms a loop with its body. It then pulls the crab through this loop repeatedly, slowly crushing it. This makes it even softer, allowing the snake to pull chunks off. The snake also tears off the crab's legs and eats them separately.

Such a laborious method lets the cat-eyed water snakes eat larger prey than other snakes their size - up to four times bigger than what they could swallow whole, giving them access to a food resource inaccessible to its competition.

"These crabs are huge! The legs alone were nearly as big as the snake's gape," Jayne said.

In fact, the team studied two other snakes living in the same area. All three belong to the Homalopsidae family of venomous, mud-dwelling crustacean-eating snakes, but they pursue different types of prey.

The white-bellied mangrove snake (Fordonia leucobalia) eats small, hard-shelled crabs by swallowing them whole; and Cantor's water snake (Cantoria violacea) eats snapping shrimp, also by swallowing them whole.

But although the white-bellied mangrove snake may seem to eat more conventionally than its cat-eyed cousin, it also has some bizarre snake table manners.

Rather than striking with an open mouth, like most snakes, the mangrove snake strikes with its chin to pin small crabs. Then it coils around the crab, its tough belly resistant to the crab's spikiness, to swallow it at leisure.

When the team got the snakes to vomit up their meals - a common technique for ascertaining snake diets - some of the crabs even came up still alive, and scuttled away.

This means that the snake, contradictory to previous thought, does not crush the crabs with its jaws before swallowing them.

All this is not just gruesome snake food research, either. The study is a fascinating look at a concept called convergent evolution, wherein related species evolve different traits to exploit their ecological niches.

"It really tests the idea of convergent evolution," says study co-author Harold Voris of the Field Museum of Natural History.

"Do we see similar types of behaviours and morphologies and hunting tactics in different geographic areas? Or are there important differences that suggest it came about differently?"

The team's research has been published in the Biological Journal of the Linnean Society.