A cave in Jerusalem's western hills might have once been a divine prophecy site where Roman-era gentiles attempted to communicate with the dead.

Three skulls and more than 100 ceramic lamps were found squeezed into the cave's crevices, and two archaeologists in Israel speculate in a new paper that these were likely used to conjure up dead spirits and their secrets – a practice known as necromancy.

The Te'omim Cave has been studied since 1873, and experts have long suspected that the spring water that flows through the underground system was considered healing to those who used the cave between 4000 BCE and the fourth century CE.

Only in the 1970s, however, did archaeologists uncover a series of secret passageways leading to other, hidden inner chambers.

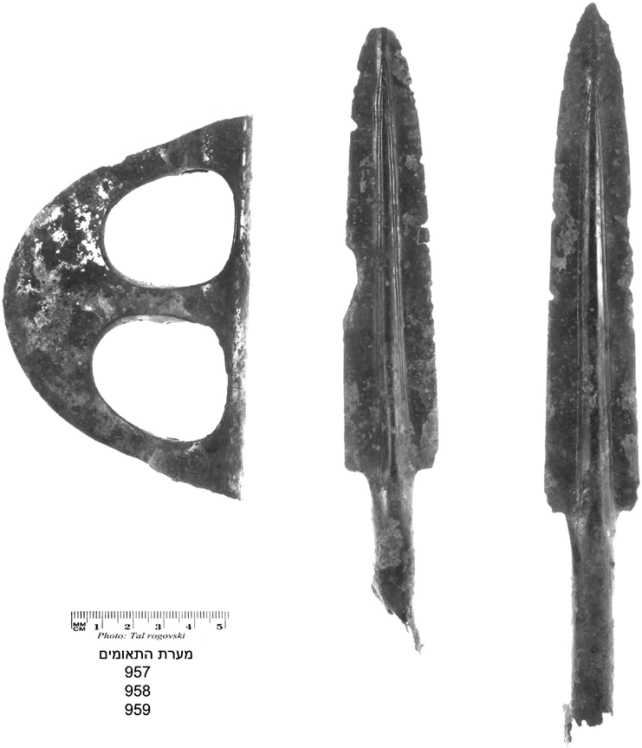

Long, narrow crevices were abundant in these concealed areas, and they housed embedded archaeological artifacts such as coins, pottery, metal weapons, and, importantly, lamps and skulls.

The few human remains weren't exactly on display. One skull was found with four late Roman-era lamps tucked deep into a crevice that was particularly hard to reach, for instance.

Archaeologists had to use long poles with iron hooks to recover these items from their hiding spot.

Because the lamps were buried so far into the rock, it's doubtful they were used for lighting the cave.

Instead, ancient writings from the time suggest that the movement of flames was once considered a key way to communicate with demons, spirits, or gods.

Skulls were also commonly associated with sorcery, and daggers, swords, and axes were thought to protect believers from evil spirits.

"The Te'omim Cave in the Jerusalem hills has all the cultic and physical elements necessary to serve as a possible portal to the underworld," write Eitan Klein from the Israel Antiquities Authority at Ashkelon Academic College and Boaz Zissu from Bar-Ilan University.

Previous studies on the cave have theorized that this was once a sacred place of worship for an underworld deity, but it wasn't until three human skulls were found that archaeologists began to suspect ritual magical practices took place here as well.

Written sources from ancient Roman and Greek times suggest that necromancy was commonly practiced by witches in tombs or underground shrines, and skulls were a key feature.

On the Greek island of Lesbos, for instance, an ancient passage suggests that the skull of Orpheus was "lodged in a chasm", where it sang "its prophecies in an earthen chamber."

Other Greek writings from the fourth and fifth centuries discuss spells to seal the mouths of skulls so they can no longer speak.

Parallel discoveries in Jewish history specifically are not nearly as common; however, there is evidence that rabbis at this time knew that skulls were used for necromancy in the Greco-Roman world.

Caves, in fact, were considered key places of idolatry by Jewish religious leaders. One famous text on Jewish oral traditions suggests that as many as 80 women working in a cave south of Tel Aviv were once hanged for their underground witchcraft.

"As far as we know, other than the use of skulls for sorcery and necromancy, rituals involving human skulls are hardly ever mentioned in classical sources," the two archaeologists note.

As such, the cave's unusual combination of artifacts is highly suggestive of ancient divination.

The study was published in the journal Harvard Theological Review.