Pyroptosis, a type of programmed cell death related to infection and an inflammation response, can actually be stopped and managed, according to new research – whereas it was previously thought that the process was irreversible once it gets going.

Killing off cells with pyroptosis is something the body uses to stay healthy, though such methods can also be hijacked to cause damage. What makes studying cell death challenging is the unpredictability of how it's initiated, along with the varying kinds of effects it has in different cells and different people.

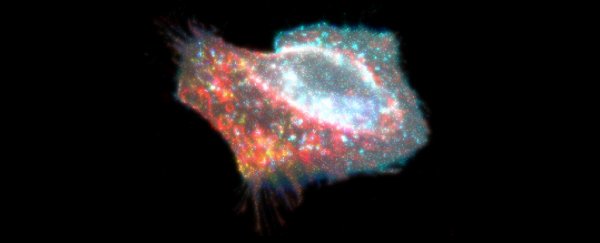

The research team here used a new way of analyzing pyroptosis, creating a custom-made version of a protein linked to cell death that responded to light. Lab experiments revealed signs of pyroptosis dynamically self-regulating in response to external circumstances.

"This showed us that this form of cell death is not a one-way ticket," says pharmacologist Gary Mo from the University of Illinois Chicago. "The process is actually programmed with a cancel button, an off-switch."

The protein created for the study was an optogenetic (light-responsive) version of gasdermin, key to the biochemical reactions that make up pyroptosis. It opens large pores in cell membranes in order to kill them off when instructed by the body.

Using fluorescent imaging technology to precisely activate their bespoke gasdermin, the researchers could see that under certain conditions – like a specific concentration of calcium ions, for example – the opened pores closed back up again in seconds.

While it's still early days in terms of figuring out why this happens and the exact circumstances that trigger it, it's evidence that pyroptosis can start and then stop again depending on what else is happening around it.

"Our optogenetic gasdermin allowed us to skip over the unpredictable pathogen behavior and the variable cellular response because it mimics at the molecular level what happens in the cell once pyroptosis is initiated," says Mo.

Several diseases, including some cancers, are the result of malfunctioning cell death processes that aren't working as they should. This malfunctioning can also cause inflammation to get out of control after an infection – as with sepsis, for example.

An improved knowledge of how cell death works – and pyroptosis is one of the major types – could lead to improved treatments as well, if we're able to find ways of controlling which cells are getting killed off and when.

Previous research has revealed ways in which bacteria can avoid the attacks of pyroptosis and apoptosis (another type of cell death), and as pathogens get smarter it's important that we continue to have the drugs to beat them.

"Understanding how to control this process unlocks new avenues for drug discovery, and now we can find drugs that work for both sides," says Mo.

"It allows us to think about tuning, either boosting or limiting, this type of cell death in diseases, where we could previously only remove this important process."

The research has been published in Nature Communications.