There's water on the Moon, and scientists have just confirmed where a lot of it may be hiding.

A mineral in Moon dust collected by China's Chang'e-5 lander and ferried to Earth was recently found to contain so much water, it makes up 41 percent of its weight.

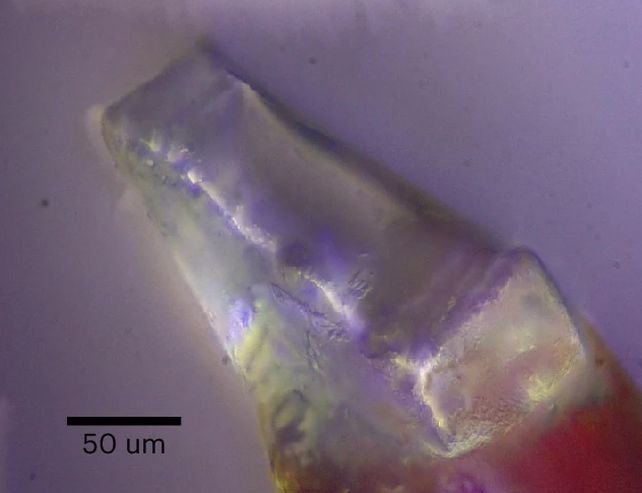

The mineral is similar to novograblenovite, which was only identified a few years ago in basaltic rock from Russia's Kamchatka Peninsula. Both the lunar and terrestrial versions have the chemical formula (NH4)MgCl3·6H2O, and have similar crystalline structures.

Given that we can study novograblenovite right here on Earth, the discovery of an almost identical mineral on the Moon can give us some clues about where lunar water is hiding and how it got there – as well as the history of lunar H2O.

The origin, presence, and distribution of water on the Moon remain something of a mystery. It's something scientists want to figure out, because where the Moon's moisture came from and where it is now is an important component of the history of the Earth-Moon system.

In addition, knowing where water is lurking has significance for future lunar exploration missions, since humans need water for survival.

Water has been found in older lunar samples before, trapped in tiny glass beads that are produced when surface material melts and forms what are known as spherules. Detections of water signals in the spectrum of light reflected from the Moon's surface suggest there's plenty more up there, somewhere.

One prevailing notion is that water is bound up in minerals that comprise the lunar regolith. Previous studies, however, have suggested that the hydrogen and oxygen bound up in Moon dirt could be in the form of other hydroxyl molecules – compounds made up of hydrogen and oxygen in proportions different from that of water.

When it landed on the Moon in December 2020, though, Chang'e-5 made a breakthrough – the first in situ detection of what appeared to be water in a boulder on the Moon. It was unclear, though, whether the detection was actually molecular water, or another hydroxyl molecule. That required a closer analysis than what a robotic lander could provide.

Now, humans on Earth led by physicists Shifeng Jin and Munan Hao of the Chinese Academy of Sciences have performed that analysis, subjecting samples sent to Earth by the Chang'e-5 mission to X-ray crystal diffraction and chemical isotope analysis techniques to determine whether the lunar regolith contains water or something else.

Their efforts revealed the presence of molecular water, with the mineral (NH4)MgCl3·6H2O containing up to six water crystals.

Novograblenovite rarely forms on Earth, emerging from the interaction of hot basalt with volcanic gasses that are rich in water and ammonia. The lunar mineral isn't quite the same – the chlorine isotope found within it has a different composition to terrestrial chlorine isotopes – but its formation mechanism is likely to be quite similar.

This suggests a lunar source of both water and ammonia existed when volcanic activity was active in the Moon's past.

"Thermodynamic analysis shows that the lower limit of the water content in the lunar volcanic gas at that time was comparable to that of the driest volcano on Earth today, Lengai Volcano," the Chinese Academy of Sciences writes in a statement.

"This reveals a complex history of lunar volcanic degassing, which is of great significance for exploring the evolution of the Moon."

The discovery also suggests a previously unknown source of water on the Moon – hydrated salts. This is much more stable than water ice, suggesting that it may be available even on areas of the Moon frequently bathed in sunlight, reducing our future possible reliance on water ice sequestered deep in shadowed craters at the lunar poles.

The team's findings have been published in Nature Astronomy.