A new study has shown that there are tiny genetic changes happening in our cells more than a decade before cancer is diagnosed, and they can be detected through a simple blood test.

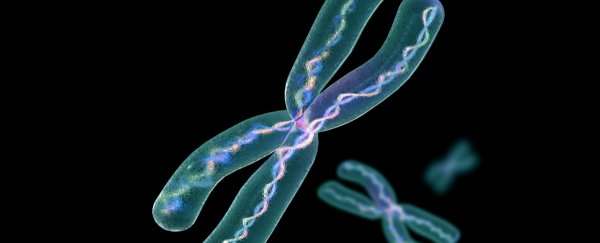

The research found that there are changes in the length of our telomeres - the protective caps at the end of our chromosomes that shrink as we age - which can predict cancer up to 13 years before symptoms develop, and they could help us to detect and fight the disease in its earliest stages.

This is the first study to progressively monitor telomere changes in people over a long period of time, and it shows that there's a unique pattern in telomere length that predicts who will go on to develop the disease.

"Understanding this pattern of telomere growth may mean it can be a predictive biomarker for cancer," the study's lead author, Lifang Hou from Northwestern University in the US, said in a press release. "Because we saw a strong relationship in the pattern across a wide variety of cancers, with the right testing these procedures could be used to eventually diagnose a wide variety of cancers."

Researchers have been trying to understand the link between telomere length and cancer for years, but have so far struggled to come up with a consistent result.

To investigate further, the team followed 792 seemingly healthy people between 1999 and 2012. By the end of the study, 135 of these participants were diagnosed with a range of cancers, including prostate, skin, lung and leukaemia. Looking back over their records, the researchers found that they could tell which would go on to develop cancer just by looking at the pattern of changes in their blood cell telomere length, which is considered a marker of biological age.

From the very start of the study, the telomeres of those who would go on to be diagnosed with cancer shrank far more rapidly, which means they were ageing faster than those who weren't developing cancer. In fact the telomeres of the future cancer-patients looked as much as 15 years older than those of their peers.

But this accelerated ageing process stopped three to four years before the cancer was diagnosed, which could explain why previous research has struggled to find a clear link between telomere length and cancer diagnosis.

The results also provide important insight into how cancer hijacks our cells. As part of the natural ageing process, each time our cells divide, our telomeres shrink. After a certain number of cellular divisions, the telomeres become so short that cells become inactive or self-destruct, while being replaced with younger, healthier cells. But it's now apparent that cancer has found a way to get around that safeguard in order to make our cells replicate uncontrollably.

"We saw the inflection point at which rapid telomere shortening stabilises," said Hou. "We found cancer has hijacked the telomere shortening in order to flourish in the body." The team's results have been published in the journal EBioMedicine.

The next step is for researchers to find a reliable way to detect this pattern of changes in telomere length. If we can achieve this, we may be able to detect signs of cancer before it ever has a chance to replicate unchecked in our body. And we don't want to get too ahead of ourselves, but that could really be a turning point in the war against cancer. Bring it on.