The outer parts of long-dead creatures don't easily make it into the fossil record. That's why this incredibly well-preserved skin of an iconic carnivorous dinosaur is such a treat – a new analysis reveals a complex coat of scales, studs, thorns, bumps and wrinkles.

The remains of this bizarre-looking predator, known as the horned abelisaurid (Carnotaurus sastrei), were first discovered in Patagonia in 1984. At the time, it was the first meat-eating dinosaur ever found with fossilized skin, and the exquisite impressions covered nearly every part of the predator, from neck to tail.

At times, the jagged surface almost resembles Australia's thorny devil (Moloch horridus), and yet the ridges on some other scales remind scientists of an elephant hide. Not anywhere is there even a hint of a feather.

Only the fossilized skin on the abelisaurid's horned head was missing; now, scientists have properly analyzed and described the discovery in close detail.

Unlike other, brief descriptions of the skin prints, the fresh analysis has found no evidence that the dinosaur's scales were arranged in irregular rows, or that they were different sizes depending on where they were found on the body (as we see on some modern lizards, for example).

For instance, the scales don't get smaller as they spread further down the tail and away from the core of the dinosaur's body. Instead, the largest scales appear randomly scattered across the thorax and the tail.

A new artist's reconstruction of Carnotaurus, with scaly skin. (Jake Baardse)

A new artist's reconstruction of Carnotaurus, with scaly skin. (Jake Baardse)

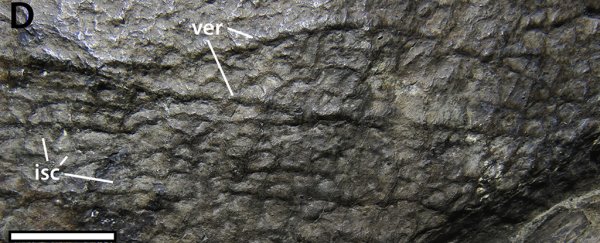

"By looking at the skin from the shoulders, belly and tail regions, we discovered that the skin of this dinosaur was more diverse than previously thought, consisting of large and randomly distributed conical studs surrounded by a network of small elongated, diamond-shaped or subcircular scales," describes paleontologist Christophe Hendrickx from the Unidad Ejecutora Lillo in San Miguel de Tucumán.

Despite feathered dinosaurs being more commonplace than we once assumed, not all of these prehistoric creatures evolved such flashy decorations.

Even dinosaurs who came from the same branch as modern birds didn't necessarily possess feathers. Large, terrestrial carnivores, such as the T. rex and the horned abelisaurid, really did seem to have scaly, lizard-like skin.

Both of these iconic predators belonged to a branch of hollow-boned, two-legged dinosaurs known as theropods, which modern birds later branched from.

But this specimen of C. sastrei has the best-preserved skin of any non-avian theropod, researchers say. Altogether, it includes six fragments of skin taken from the neck, the shoulder girdle, the thorax, and the tail.

Location of the specimens with skin. (Jake Baardse)

Location of the specimens with skin. (Jake Baardse)

The largest patch comes from the anterior part of its tail. Here, the smallest scale measures only 20 millimeters in diameter, and yet sometimes these tiny flakes of skin can be found smooshed between other scales twice as large.

These much bigger, feature scales are almost domed in appearance, akin to the domed scales found on Diplodocus – a long-necked herbivorous dinosaur. Others are shaped more like diamonds, with much longer lengths than widths; these resemble the scales seen on tyrannosaurids that also lived in the Late Cretaceous, roughly 70 million years ago.

Why the horned abelisaurid once possessed such a wide range of large and small scales is another mystery altogether.

In 1997, scientists suggested the large, conical scales found on Carnotaurus existed for "some degree of protection during confrontation", but the authors of this new analysis say these scales would do little good against teeth.

"Alternatively, in Carnotaurus and more broadly among dinosaurs, feature scales may simply have served a display/coloration function," they suggest.

This is similar to the feathers on modern birds, which can serve as mere displays or for flight. Given that feathers are thought to have evolved from scales, such similar diversity may be no coincidence.

The scales of C. sastrei (A-E) compared to other dinosaurs. (Hendrick and Bell, Cretaceous Research, 2021)

The scales of C. sastrei (A-E) compared to other dinosaurs. (Hendrick and Bell, Cretaceous Research, 2021)

Yet other comparisons are harder to pin down. Some of the most intriguing scales on the horned abelisaurid, for instance, come from its tail, where certain flakes contain an arrangement of vertical ridges or grooves.

The authors say these parallel lines look almost like the wrinkles on elephant skin, and given that both the theropod and the African elephant are large terrestrial animals without sweat glands living in warmer climates, the authors suspect these ridges may hold similar functions. (African elephants have wrinkles on their skin to increase surface area and more effectively shed excess heat via evaporation.)

"While we do not claim that Carnotaurus and elephants necessarily thermoregulated in the same ways (i.e. using evaporative cooling), we note here that they share distinct gross morphological similarities in their integument, despite one having scales and the other having a highly modified mammalian epidermis," the authors write.

Regardless of the specifics, they maintain theropod skin is likely to have played at least some role in thermoregulation. Future research on the scaly skin of early dinosaurs may reveal far more than simply what they looked like. It might also tell us how they lived.

The study was published in Cretaceous Research.