The childcare system of a contemporary hunter-gatherer community suggests a major pitfall of the nuclear family, and it could hint at why so many parents in wealthy, Western nations feel burned out.

A team of researchers, led by evolutionary anthropologist Nikhil Chaudhary from the University of Cambridge, argues that children may be "evolutionarily primed" to expect more attention and care than just two parents can provide.

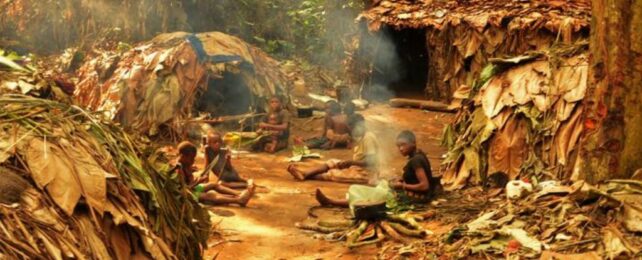

Investigating the culture of Mbendjele hunter-gatherers, who live in the northern rainforests of the Republic of Congo and subsist on hunting, fishing, gathering, and honey collecting, researchers found a widespread caregiving network.

Among 18 infants and toddlers in this community, researchers noticed that each child receives, on average, nine hours of attentive care and physical contact each day, usually from around 10 individuals, but sometimes from more than 20.

The sheer number of individuals attuned to a single child's needs meant that the infant's cries were usually responded to in just 25 seconds.

The biological mother of any given child was only on the hook for roughly 50 percent of these crying episodes. The rest of the time, someone else helped care for the child, oftentimes older kids or adolescents.

While this one contemporary community in Africa may not be representative of all hunter-gatherer communities in human history, its care-giving ratio is similar to other modern hunter-gatherer societies.

While these cultures are firmly situated in the present and not true 'relics of the past', they can give important clues about what social structures might have looked like more than 10,000 years ago before the dawn of agriculture.

For the vast majority of human history, our species has lived as hunter-gatherers, which means for most of human existence, mothers and fathers probably had way more support raising kids than they do today in most wealthy, Western nations.

How much more support is hard to say.

To date, most research on child attachment has focused only on western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic (WEIRD) populations, which means experts are missing the full picture of the human experience.

Among some contemporary hunter-gatherer societies, like the Mbendjele and the !Kung in southern Africa, there seems to be exceptionally high responsiveness to crying babies.

In WEIRD societies, on the other hand, the levels of responsiveness seem to be lower.

"If an individual now experiences relatively lower access to [caregiving], this may result in the activation of evolved psychological responses associated with adversity (which may or may not still be adaptive); or if access is low enough, it may lead to psychological dysregulation," Chaudhury and colleagues hypothesize.

That idea requires much more research. Chaudhary himself cautions that human psychology has evolved to be flexible, and there may not be just one specific way of life that suits our health and well-being best.

What is beyond debate, however, is that the nuclear family system, as Chaudhary puts it, "is a world away from the communal living arrangements of hunter-gatherer societies like the Mbendjele."

"Crying was virtually always responded to, usually very swiftly; and responses typically took the form of comforting or feeding, rarely stimulating, and never controlling," the team of researchers writes.

By contrast, in WEIRD societies, parents are usually on their own when responding to a distressed baby, which could breed profound exhaustion or depression.

Whether or not these different childcare systems actually have adverse impacts on the child or parent is unclear and demands further comparative research.

The researchers behind the current study say future work should dig into the psychological development and well-being of hunter-gatherer children in comparison to WEIRD children, as well as whether care from mothers differs to care from non-maternal caregivers.

"As a society, from policymakers to employers to healthcare services," Chaudhary says, "we need to work together to ensure mothers and children receive the support and care they need to thrive."

The study was published in Developmental Psychology.