In 1670, a new object lit up the Northern sky. Later known as CK Vulpeculae, or Nova Vulpeculae 1670, it became famed as the earliest example of a well-documented nova.

The only problem with that? It's not a nova after all. Instead, the object was produced by the incredible collision between a brown dwarf and a white dwarf.

Novae are the result of an interaction in a binary pair, most commonly where one of the stars is a main sequence star - a star that is producing hydrogen fusion in its core - and the other is a white dwarf, the evolutionary end-point of a Sun-like star, where hydrogen fusion has sputtered out.

If these two draw close enough together, the white dwarf begins pulling material from its companion star until the pressure and temperature are both high enough to trigger fusion reactions - which creates a runaway thermonuclear reaction. Boom.

In 2015, astronomers announced that they had probed the gas surrounding the object, and suspected that this wasn't the mechanism that had produced the object we thought was a nova.

Instead, they proposed, it was created not by a star cannibalised by a white dwarf, but a collision between two main sequence stars.

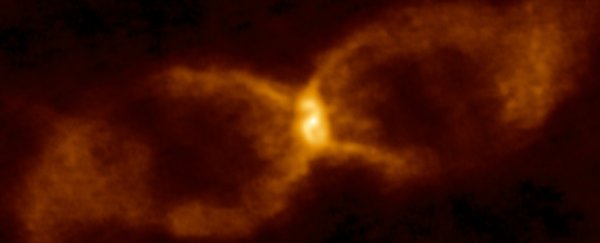

Wrong again. According to an international team of researchers, that's not what happened either. Using the Atacama Large Millimeter-Submillimeter Array (ALMA), they probed the hourglass-shaped debris produced by the event, and concluded that the two objects were a brown dwarf and a white dwarf.

A white dwarf, as we already mentioned, is a dead star that is no longer producing hydrogen fusion, the dominant process that generates energy in stars, its core instead supported by electron pressure.

A brown dwarf is thought to be a star that couldn't quite get started. It's too small to produce hydrogen fusion, but still large enough for deuterium fusion, a lower temperature process vital to newly forming stars.

"It now seems what was observed centuries ago was not what we would today describe as a classic 'nova,'" said astronomer Sumner Starrfield of the Arizona State University.

"Instead, it was the merger of two stellar objects, a white dwarf and a brown dwarf. When these two objects collided, they spilled out a cocktail of molecules and unusual isotopes, which gave us new insights into the nature of this object."

By studying these isotopes, the researchers have reconstructed what they think the binary system and its demise looked like.

"The presence of lithium, together with unusual isotopic ratios of the elements carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen, point to material from a brown dwarf star being dumped on the surface of a white dwarf," explained astronomer Stewart Eyres of the University of New South Wales in Australia.

According to the reconstruction, the white dwarf, while much smaller in size than the brown dwarf, was about 10 times more massive than its companion, with much greater gravity.

As the two stellar objects grew closer together in their mutual orbit, the white dwarf's tidal force ripped the brown dwarf apart.

Almost immediately, the white dwarf would have ejected some of the material from the brown dwarf, with the remainder forming an accretion disc falling into the white dwarf. This, in turn, would result in jets, which would blow the ejected material into the hourglass shape we see today.

Further supporting this hypothesis is the presence of organic molecules such as formaldehyde and formamide. These, the researchers said, would not survive in a nuclear fusion environment - which is an essential part of a nova.

But if a brown dwarf and a white dwarf collided, these molecules could have been produced by the resulting explosion, and survive in the cloud of debris for astronomers to study centuries later.

The research has been published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.