As we get older, the essential cleaning processes that our brains need to keep functioning start to break down and fail. In new research, scientists have figured out how to boost waste removal cycles in the brains of mice – with dramatic effects on their memory.

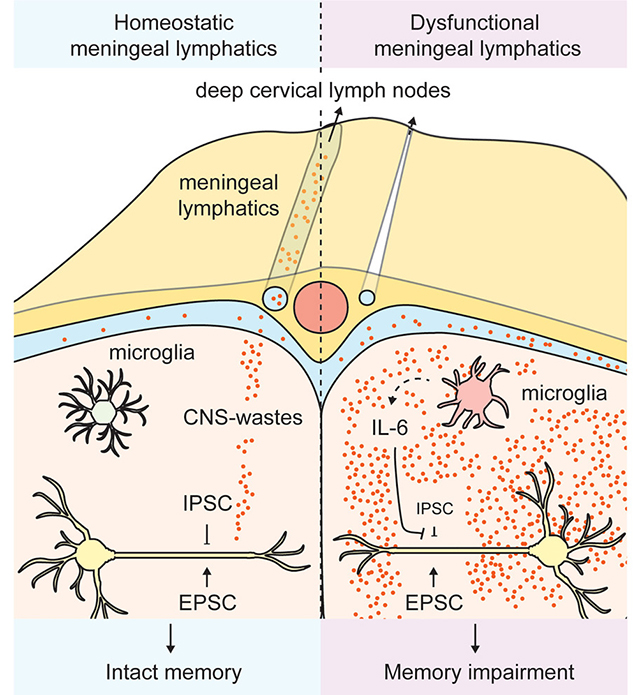

Led by a team from Washington University in St. Louis, the research focuses on vessels around the brain called meningeal lymphatics, the brain cleaners in chief. These vessels are part of the larger lymphatic system in the body, responsible for waste disposal and helping the immune system.

The researchers used a targeted protein treatment on older mice to help these meningeal lymphatics grow and operate. In subsequent experiments, the treated mice were shown to have improved memory function compared to untreated animals.

There's a clear link to neurodegenerative conditions like Alzheimer's here, conditions in which aging brains lose memory functions and cognitive abilities. This new work could potentially offer some clues as to how to slow down or prevent dementia.

"A functioning lymphatic system is critical for brain health and memory," says neuroscientist Kyungdeok Kim, from Washington University in St. Louis.

"Therapies that support the health of the body's waste management system may have health benefits for a naturally aging brain."

The team also discovered that the protein interleukin 6 is used as a kind of distress signal by overwhelmed immune cells called microglia – a distress signal that's sent out when the brain's cleaning apparatus gets overwhelmed.

As well as boosting the mice's memory, the lymphatics treatment reduced interleukin 6 levels, restoring order to this part of the immune system and preventing some of the damage in the brain caused by stressed microglia.

Another important aspect of the research: the meningeal lymphatic vessels are just outside the brain, so they can be targeted without the complexity of having to get through the blood-brain barrier that helps keep the brain protected.

"The physical blood-brain barrier hinders the efficacy of therapies for neurological disorders," says neuroscientist Jonathan Kipnis, from Washington University in St. Louis.

"By targeting a network of vessels outside of the brain that is critical for brain health, we see cognitive improvements in mice, opening a window to develop more powerful therapies to prevent or delay cognitive decline."

These are all important insights into how normal brain communication networks get disrupted when toxic material isn't cleared away, and allowed to build up. It's not unlike trash building up on railway lines and stopping trains from traveling.

The new findings fit in neatly with previous research too, including a 2022 study in which mouse memories were boosted through injections of cerebrospinal fluid – the same fluid meningeal lymphatic vessels clean waste from.

"We may not be able to revive neurons, but we may be able to ensure their most optimal functioning through modulation of meningeal lymphatic vessels," says Kipnis.

The research has been published in Cell.