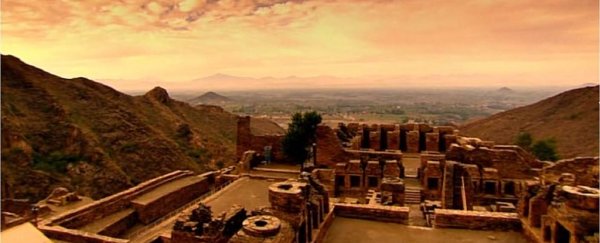

Some 4,000 years ago, a thriving civilisation in the Indus River Valley inexplicably abandoned its cities, leaving their empty buildings to decay.

The Harappa culture (of what is now Pakistan) had a booming local economy and long-distance intercultural trade. Yet, by around 1800 BCE, they had moved from their cities with mod cons such as advanced sewage systems, to smaller villages around the Himalayan foothills.

The reason for this baffling downgrade, according to researchers, was a changing climate - it had driven them out of their homes.

But, unlike the high rate of climate change we are experiencing today, it wasn't warming that was responsible. Rather, a mini ice age induced changes in the thermal balance between the hemispheres, increasing the number of winter monsoons while gradually drying up the summer ones.

This, in turn, had a negative impact on agriculture, making it difficult for the Harappa to grow enough to feed their population. So they did the only logical thing - they moved on.

"Although fickle summer monsoons made agriculture difficult along the Indus, up in the foothills, moisture and rain would come more regularly," says geologist Liviu Giosan of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute.

"As winter storms from the Mediterranean hit the Himalayas, they created rain on the Pakistan side, and fed little streams there. Compared to the floods from monsoons that the Harappans were used to seeing in the Indus, it would have been relatively little water, but at least it would have been reliable."

The evidence for this monsoonal shift comes from ancient sediments from under the floor of the Arabian Sea. Giosan and his team took core samples from several sample sites, and studied the sediment layers to look for a particular sign of winter monsoons.

That sign is a type of shelled, unicellular plankton called foraminifera, or forams for short. When monsoon comes in winter, there's a surge in plant and animal life in the oceans; strong winds bring nutrients from deeper in the ocean up to the surface via a process known as upswelling.

These fossilised forams in the sediment cores have provided evidence of these winter monsoons. Once this was identified, the team was able to look at DNA preserved in the sediments.

Because it's a low-oxygen environment, this DNA was very well preserved - basically a snapshot of everything that lived there.

"The value of this approach is that it gives you a picture of the past biodiversity that you'd miss by relying on skeletal remains or a fossil record," said paleontologist and geobiologist William Orsi of Ludwig Maximilian University in Munich, Germany.

"And because we can sequence billions of DNA molecules in parallel, it gives a very high-resolution picture of how the ecosystem changed over time."

Sure enough, they were able to trace the gradual increase in winter monsoons and the decline in summer monsoons to the end of the Harappa's time in the Indus River Valley.

We don't know how they moved, or how long it took, but one thing is certain: the foothills of the Himalayas couldn't sustain them long-term, either. Eventually the rains there dried up too, and the Harappa culture died out.

"We can't say that they disappeared entirely due to climate - at the same time, the Indo-Aryan culture was arriving in the region with Iron Age tools and horses and carts. But it's very likely that the winter monsoon played a role," Giosan said.

We know that climate change has played a role in migration many times throughout history. Ice ages contributed to early Homo sapiens migrations out of Africa, and climate fluctuations affected agriculture in the Ancient Near East over several millennia.

Changing climate also played a key role in the Great Famine of 1315, which brought medieval Europe to its knees.

This new discovery is a warning we would do well to heed, Giosan noted.

"If you look at Syria and Africa, the migration out of those areas has some roots in climate change," he said.

"This is just the beginning - sea level rise due to climate change can lead to huge migrations from low lying regions like Bangladesh, or from hurricane-prone regions in the southern US.

"Back then, the Harappans could cope with change by moving, but today, you'll run into all sorts of borders. Political and social convulsions can then follow."

The team's research has been published in the journal Climate of the Past.