Brazil's bats are harboring a vast and diverse pool of coronaviruses, a new study finds, including a newly identified strain that may pose a danger to human health in the years to come.

Scientists are taking the threat seriously and will soon conduct testing in a secure lab to see if the variant really could spill over to our own species.

The discovery is cause for concern because the strain is eerily reminiscent of the bat-borne virus behind Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) – a contagion that causes a very high case fatality rate of nearly 35 percent in humans.

Since its identification in 2012, the MERS coronavirus (MERS-CoV) has caused 858 known deaths, mostly in the Middle East, Africa, and South Asia. While mild cases are likely underreported, this virus holds the highest case fatality rate of all the known coronaviruses that can infect humans, making it the most lethal.

For comparison, the coronavirus responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic, SARS‑CoV‑2, has a human case fatality rate of around 2 percent, according to a 2022 study.

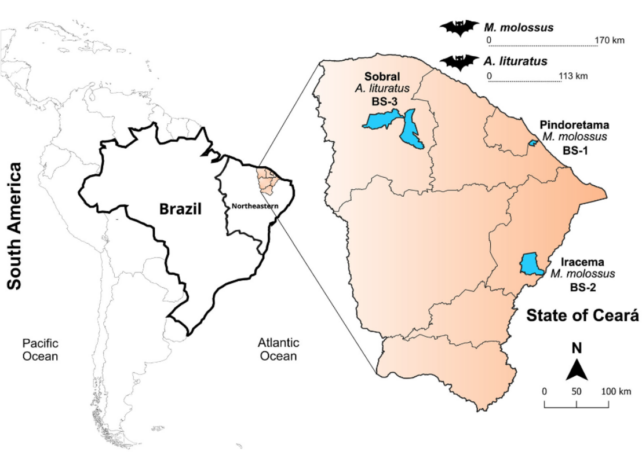

Scientists in Brazil and China discovered the close relative of MERS-CoV while testing 16 different bat species in Brazil for pathogens.

Taking more than 400 oral and rectal swabs from bats, the international team, led by Bruna Stefanie Silvério from the Federal University of São Paulo, identified seven distinct coronaviruses. These were harbored by just two species: Molossus molossus (an insect-eater) and Artibeus lituratus (a fruit bat).

Only one of the viral variants shares an evolutionary history with MERS-CoV.

Until now, members of the MERS-CoV family had only been documented in bats of Africa, Europe, and the Middle East.

This indicates that "closely related viruses are circulating in South American bats and expanding their known geographic range," according to the authors.

Scientists have known that viruses found in bats are a threat to human safety since long before the 2020 pandemic.

In 2002, severe acute respiratory syndrome, or SARS, became the first pandemic transmissible disease in the 21st century to have an unknown origin. The fatality ratio of this viral outbreak reached around 10 percent by the end of the epidemic in June 2003.

Later, researchers figured out that bats were a natural reservoir for SARS-like coronaviruses, and after years of hard work, they confirmed that SARS-CoV-1 spilled over from these wild mammals to ourselves.

In 2012, yet another deadly coronavirus appeared on the scene. The MERS coronavirus was first identified in Saudi Arabia after most likely jumping from bats to camels to humans.

While this virus spreads less easily among our own species, travelers have carried the infection to the United States, Europe, Africa, and Asia.

The discovery of a MERS-like strain in South America underscores the "critical role bats play as reservoirs for emerging viruses," write Silvério and her team.

"Right now we aren't sure it can infect humans, but we detected parts of the virus's spike protein [which binds to mammalian cells to start an infection] suggesting potential interaction with the receptor used by MERS-CoV," explains Silvério.

"To find out more, we plan to conduct experiments in Hong Kong during the current year."

Since 2020, the world has taken the threat of coronaviruses spilling over from wild mammals to humans more seriously than ever before. The discovery of a threatening bat-borne virus in South America is certainly concerning, but it's also a point of comfort. Now that we know it exists, scientists can keep a close eye on the threat.

"Bats are important viral reservoirs and should therefore be submitted to continuous epidemiological surveillance," argues co-author Ricardo Durães-Carvalho, biologist at the Federal University of São Paulo.

Better the devil you know than the one you don't.

The study was published in the Journal of Medical Virology.