Additives that are commonly found in ultra-processed foods could be increasing the risk of type 2 diabetes when mixed together in certain ways, new research has shown – which may prompt a rethink in health guidelines for additive use.

Led by a team from Sorbonne Paris North University in France, the research adds to a growing body of evidence scrutinizing the potential health impacts of these additives – which are used to make foods last longer and taste better.

"Mixtures of food additives are daily consumed worldwide by billions of people," write the researchers in their published paper. "So far, safety assessments have been performed substance by substance due to lack of data on the effect of multi-exposure to combinations of additives."

"Our objective was to identify most common food additive mixtures, and investigate their associations with type 2 diabetes incidence in a large prospective cohort."

The researchers looked at public health data from 108,643 people followed for an average of almost 8 years, charting diet records against cases of type 2 diabetes. Computer algorithms were used to calculate the mixtures of additives across eating habits.

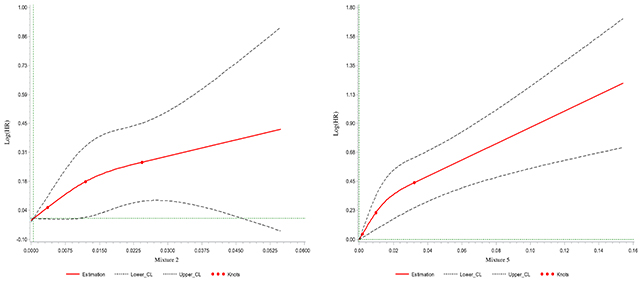

Two of the five additive combinations analyzed were linked to an increase in type 2 diabetes risk. The first, a mix including modified starches, guar gum, and carrageenan, which is often found in broths, dairy desserts, and sauces, was associated with an 8 percent higher risk.

The second was a mixture including citric acid, sodium citrates, and artificial sweeteners, which is often found in soft drinks and sweetened beverages. It was associated with a 13 percent higher risk of getting type 2 diabetes.

As usual with studies structured like this, the data doesn't show direct cause and effect – that it's these additives specifically causing more cases of type 2 diabetes. However, the associations are significant enough to raise concerns.

"To our knowledge, these findings provide the first insight into the food additives that are frequently ingested together (due to their co-occurrence in industrially-processed food products or resulting from the co-ingestion of foods in dietary patterns) and how these additive mixtures may be involved in type 2 diabetes etiology," write the researchers.

There are some major limitations to the study. The majority of the participants here were women, and it's not clear how far these findings might extend more generally – across other countries, for example, where food regulations vary. There's also the difficulty of exactly calculating additive mixes and overlap across so many dietary patterns.

"The observed associations are both less than 20 percent, so residual confounding is likely a significant problem within this study," says Alan Barclay, Honorary Associate at the University of Sydney, who was not involved with this work.

That said, it raises an issue that's barely been looked at before: how additives might combine in the way they influence our health. Further research could look at the reasons behind this association, and how it adds to what we know about the harms of ultra-processed foods.

"These findings suggest that a combination of food additives may be of interest to consider in safety assessments, and they support public health recommendations to limit non-essential additives," write the researchers.

The research has been published in PLOS Medicine.