Cognitive tests before and after use of a medication prescribed for mood disorders suggests these antidepressants may improve our thinking abilities.

Millions of people use selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) to treat anxiety and depression. But their use is controversial for a number of reasons, including lack of data on their long term efficacy and because we don't fully understand how they work.

So Copenhagen University psychologist Vibeke Dam and colleagues took a closer look at the drug's impacts on 90 patients with moderate to severe depression using brain scans and cognitive and mood assessments before and after taking SSRIs for eight weeks.

Once the study's volunteers had received initial assessments they were prescribed a daily dose of the SSRI escitalopram. The scans were then repeated at the end of an eight week treatment period for 40 of the patients, followed by the final round of cognitive and mood assessments at week 12.

Following the treatment period, patients had almost a 10 percent reduction in the cell receptors that the SSRI bind to compared to how many were detected before they were put on the medication. The patients also showed improvements in the memory cognitive tests, particularly in their ability to recall words.

But it was those patients who experienced the least amount of change in the serotonin receptor known as 5HT4 whose verbal memory improved the most. Curiously, changes in the receptor binding did not correlate with improvements in mood.

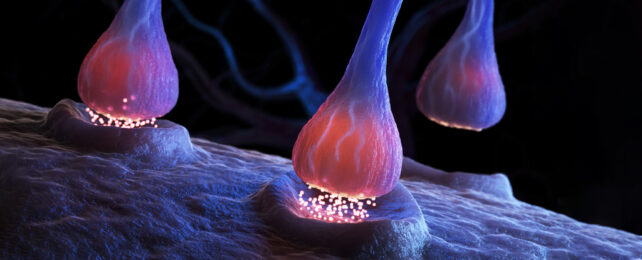

The researchers suggest that the SSRI treatment may counteract reduced receptor levels by increasing serotonin in the synapses, leading to the remaining serotonin receptors (including 5-HT4) becoming more efficient.

"Our work ties the improvement in cognitive function to the specific 5HT4 receptor," explains Dam.

"Direct serotonin 4 receptor stimulation may be an important pro-cognitive target to consider in optimizing outcomes of antidepressant treatment."

The researchers previously showed unmedicated patients with major depressive disorder as well as healthy patients with a family history of the condition have less of these receptors than healthy populations. Dam and team suggest this may explain why people with depression often have difficulties with their memories.

"This is a first result, so we need to do a lot more work to look at the implications," cautions Copenhagen University neurobiologist Vibe Froekjaer.

What's more, ethical restrictions prevented the use of a placebo alternative to the use of the antidepressant, reducing certainty that the outcomes the researchers saw were entirely due to the effects of the SSRIs.

Nevertheless, "this work points to the possibility of stimulating this specific receptor so that we can treat cognitive problems, even aside from whether or not the patient has overcome the core symptoms of depression," Froekjaer continues.

While the patients showed some improvement in their depression, the fact any mood changes didn't scale with the changes in the 5HT4 receptors raised doubt over whether this mechanism is responsible for SSRIs' clinical effects.

Whether SSRIs are even therapeutic for depression is now in question given several studies have now found there's no evidence they work any better than a placebo, and the whole idea of serotonin being involved in depression at all is now being questioned.

No one should stop SSRIs without first consulting a doctor, as this can have serious side effects. Besides, we also can't know for sure they're not working in a way researchers have just yet to figure out.

But, given so many of us depend on these drugs, it is important we keep trying to understand what they're really doing.

"Future studies are needed to further illuminate antidepressant mechanisms of action of both SSRI and alternative strategies to advance precision psychiatry for major depressive disorder," the researchers write in their paper.

This research was published in Biological Psychiatry.