The humble mushroom is a fungi with plenty of potential. Previous research has shown mushrooms can reduce depression risk, improve brain cell growth, and guard against cancer – and a new study shows they may protect against influenza too.

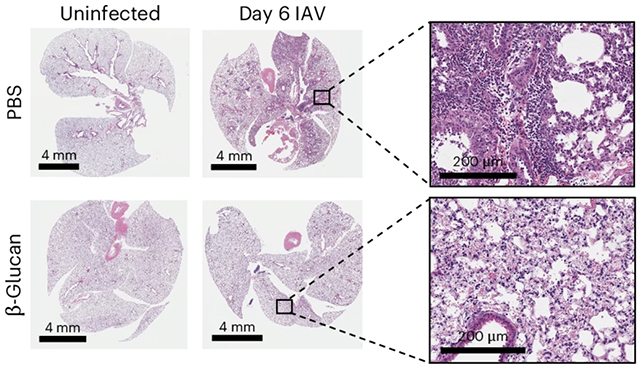

Researchers led by a team from McGill University in Canada found that the beta-glucan fibers found in all types of mushrooms could act as a sort of barrier to flu, limiting inflammation in the lungs of mice exposed to infection after a dose of beta-glucan.

What's more, the mice given the fibers showed improved lung function and a lower risk of serious illness and death when hit with the flu. Human trials will tell us more, but this is already a promising avenue for researchers to explore.

"Beta-glucan is found in the cell walls of all fungi, including some that live in and on our bodies as part of the human microbiome," says Maziar Divangahi, immunologist at McGill University.

"It is tempting to hypothesize that the levels and composition of fungi in an individual could influence how their immune system responds to infections, in part because of beta-glucan."

Beta-glucan is already known to boost immunity, but here the researchers wanted to test its capabilities in terms of disease tolerance – essentially reducing the impact of the viral attack on the body, rather than killing off the attacking pathogens, as conventional antiviral treatments do.

What makes beta-glucan even more special is that it seems to reprogram immune cells to better cope against the flu. Treated mice had more immune cells called neutrophils, but they were behaving in a more controlled manner than normal.

The researchers say that reprogramming was crucial, limiting the risk of neutrophils going into overdrive to fight off infection – and leading to the lung inflammation that so often causes complications and serious health issues (like pneumonia) after a flu infection.

"Neutrophils are traditionally known for causing inflammation, but beta-glucan has the ability to shift their role to reduce it," says immunologist Kim Tran, from McGill University.

The smarter, savvier neutrophils stuck around for up to a month as well, hinting that a treatment based on beta-glucan could offer long-lasting protection – though we're still in the very early stages of understanding its potential in this area.

While we know the benefits of disease tolerance – and how it can save lives – there's a lot we don't know about how it works behind the scenes. This research adds a host of useful insights, and could well be applied to other similar respiratory diseases in future studies.

"It is remarkable how beta-glucan can reprogram certain immune cells, such as neutrophils, to control excessive inflammation in the lung," says immunologist Nargis Khan, who is now at the University of Calgary in Canada.

The research has been published in Nature Immunology.