Scientists are one step closer to understanding the vaginal microbiome and its links to pregnancy loss, early birth, and other health complications.

A new study has delved into bacterial vaginosis, a common condition caused by an overgrowth of certain bacterial species, to show how one particular microbe disrupts vaginal health by 'eating away' at the vagina's protective coating.

The findings from cell experiments suggest unruly resident bacteria secrete enzymes that dismantle sugar molecules, called glycans, on the surface of cells that line the vagina. Breaking down this protective layer is thought to perhaps expose individuals to the risk of infections that may trigger serious complications.

Epidemiological studies have linked bacterial vaginosis to a long list of complications anyone would want to avoid: pregnancy loss, preterm birth, pelvic inflammatory disease, sexually transmitted infections, and infertility, among others.

Gardnerella vaginalis, an anaerobic bacterial species that dominates the vaginal microbiome in people with bacterial vaginosis, has also been implicated in the condition since it was first described in the 1950s.

Yet our understanding of how bacterial vaginosis may lead to further complications hasn't really been fleshed out, in part due to the stigma around and dismissal of female sexual and reproductive health.

The condition, which in the US affects up to 30 percent of women aged 14 to 49, is treatable but often asymptomatic and commonly reoccurs.

"We knew that bacterial species implicated in bacterial vaginosis can feed on glycans in secreted mucus," explains Amanda Lewis, a vaginal microbiome researcher at the University of California (UC) San Diego School of Medicine.

"The current study allowed us to look directly at what those bacteria are then doing to the vaginal epithelial surface landscape on a biochemical and microscopic level."

Most human vaginas harbor G. vaginalis, but their overabundance in bacterial vaginosis helps form thick biofilms that other bacteria latch onto, disrupting the normal balance of microbes in the vagina.

In previous work, Lewis and her colleagues had shown how enzymes produced by G. vaginalis break down molecules in vaginal fluids and mucus.

Those molecules are an important component of the mucosal plug which blocks the opening of the uterus during pregnancy, Lewis explained in a 2020 webinar. "And so, if bacteria are able to degrade this, it may decrease the viscosity of that barrier and allow for ascending infections."

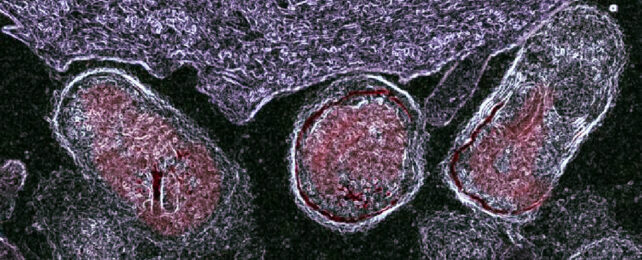

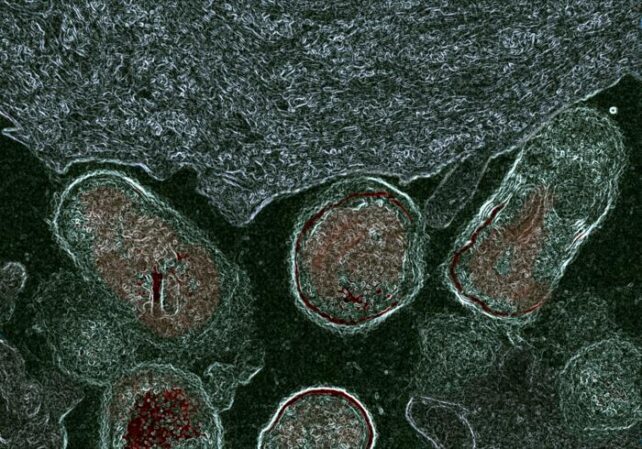

In their latest study, Lewis and her team showed Gardnerella enzymes also strip away parts of the protective glycan molecules which coat epithelial cells that line the surface of the vagina (which were cultured in the lab for these experiments).

Cells from women without bacterial vaginosis were coated in a thick layer of sugary glycans decorated with other molecules, whereas vaginal epithelial cells from women with bacterial vaginosis were sporting partially dismantled glycans.

And when the researchers treated healthy cell specimens without bacterial vaginosis with the enzymes produced by Gardnerella bacteria, they suddenly resembled the disfigured cells from women with the condition.

More research is required, but "the fact that we were able to replicate some of the effects of bacterial vaginosis suggests that we may be on the right track to finding a common cellular origin for the various complications associated with this condition," Lewis says.

The paper has been published in Science Translational Medicine.