There's still some scientific debate over when exactly complex life forms appeared on Earth, and the latest research suggests previous estimates need to be revised – by about 1.5 billion years, in fact.

That's based on a new analysis of marine sedimentary rocks in the Franceville Basin off the west coast of Africa that were deposited some 2.1 billion years ago.

The general consensus is that animals first showed up around 635 million years ago. Now, an international team of researchers has discovered that the rock samples indicate increased phosphorus and oxygen in the seawater, which has previously been linked to accelerations in evolution.

"We already know that increases in marine phosphorus and seawater oxygen concentrations are linked to an episode of biological evolution around 635 million years ago," says Earth scientist Ernest Chi Fru from Cardiff University in the UK.

"Our study adds another, much earlier episode into the record, 2.1 billion years ago."

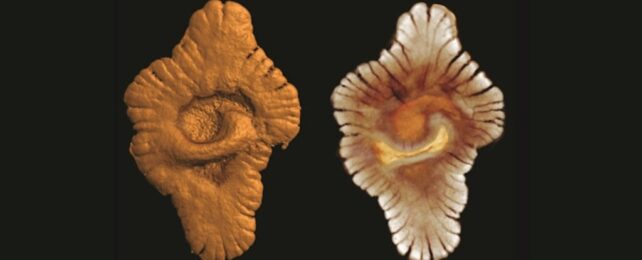

An unusually substantial number of fossils large enough to be seen without a microscope have been discovered in the Franceville Basin, and it's not clear what we're to make of them. Earlier studies have also suggested these macrofossils point to the first complex life on the planet.

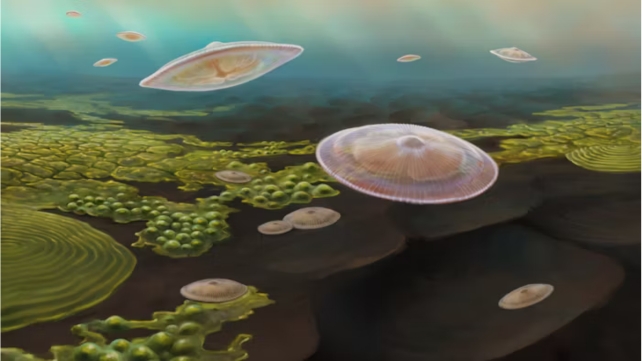

Here, the researchers link the nutrient enrichment of the water to the collision of two ancient continents, which then created a shallow inland sea and the conditions for cyanobacterial photosynthesis, a chemical process that would've led to an underwater environment more conducive to biological complexity.

This would have created a natural laboratory for organism diversity and evolutionary leaps in size and structure, the researchers contend. However, because the body of water was isolated, these more sophisticated forms of life wouldn't have spread elsewhere or survived to the next jump forward.

"We think that the underwater volcanoes, which followed the collision and suturing of the Congo and São Francisco cratons into one main body, further restricted and even cut off this section of water from the global ocean to create a nutrient-rich shallow marine inland sea," says Chi Fru.

These findings may point to complex life on Earth evolving in two steps: once following the first major atmospheric oxygen rise 2.1 billion years ago, and again following a second rise 1.5 billion years later.

In fact, complex life might have arisen several times over the millennia, as has been suggested by other studies. Scientists are still working to pin down which types of life evolved when, and there's no guarantee that all evolutionary jumps would've stuck.

Delving this far back into the past isn't easy, of course; it involves some careful analysis of ancient fossils and environments that may have harbored conditions suitable for what these researchers describe as "macrobiological experimentation".

"These observations make it possible that the appearance of macrofossils in Franceville may mark a unique window into our understanding of conditions that enabled and restricted the evolution and disappearance of Earth's earliest macrobiological life forms," write the researchers in their published paper.

The research has been published in Precambrian Research.