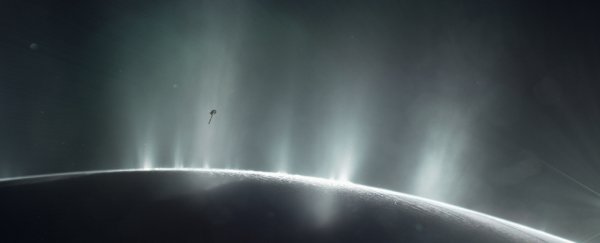

The plumes of salty water shooting out of Saturn's ocean moon Enceladus have just ponied up one of the most significant ingredients for habitability: large organic molecules rich in carbon.

It's a discovery that suggests a thin, organic rich film atop the oceanic water table - very similar to the sea surface microlayer here on Earth, which is extraordinarily rich in organic compounds.

And yes, you guessed it. These findings bolster the hypothesis that, deep under its icy crust, Enceladus could be harbouring simple marine life, clustered around the warmth of hydrothermal vents.

Previously, simple organic molecules detected on the little moon were under around 50 atomic mass units and only contained a handful of carbon atoms.

"We are, yet again, blown away by Enceladus," said geochemist and planetary scientist Christopher Glein of the Southwest Research Institute.

"We've found organic molecules with masses above 200 atomic mass units. That's over ten times heavier than methane.

"With complex organic molecules emanating from its liquid water ocean, this moon is the only body besides Earth known to simultaneously satisfy all of the basic requirements for life as we know it."

Let that sink in for a moment.

One might think that a moon far from the Sun with an ocean covered by a thick crust of ice would be an unlikely place to look for extraterrestrial life, but the case for it is mounting.

Last year, Cassini data revealed the presence of molecular hydrogen in the plumes shooting off the surface of Enceladus - a possible source of which would be the ocean's water reacting with rocks via hydrothermal processes.

That process has been observed here on Earth - around hydrothermal vents, volcanic apertures in the seafloor that spew heat into the surrounding water.

These terrestrial hydrothermal vents are often far from the life-giving light of the Sun, which triggers the photosynthesis on which the vast majority of Earth's life depends.

But the warmth from the vents allows a different process to take place - chemosynthesis. Bacteria around the vents harness chemical energy, such as the reaction between hydrogen sulfide from the vent and oxygen from the seawater, to produce sugar molecules - food.

"Hydrogen provides a source of chemical energy supporting microbes that live in Earth's oceans near hydrothermal vents," said physicist Hunter Waite of the Southwest Research Institute, principal investigator on the Cassini Ion and Neutral Mass Spectrometer.

"Once you have identified a potential food source for microbes, the next question to ask is 'what is the nature of the complex organics in the ocean?' This paper represents the first step in that understanding - complexity in the organic chemistry beyond our expectations!"

The molecules were also detected by Cassini, which sampled an Enceladus plume before it was decommissioned in September of last year.

It then used its Cosmic Dust Analyzer and Ion and Neutral Mass Spectrometer to take measurements, both of the plume and of Saturn's E ring - the planet's second outermost ring, within which Enceladus orbits. It's formed by particles escaping the moon's gravity.

It's possible that a future probe may be able to dive through the plumes, equipped with a high-resolution mass spectrometer, to analyse those molecules in greater detail, and with more advanced technology.

Meanwhile, researchers here on Earth are continuing to observe and experiment on hydrothermal vents in the hopes of advancing our understanding of what life on Enceladus might look like.

And there are a number of proposed missions to actually send a craft to the ice moon to investigate more closely the possibility of life - and maybe even find it. But sadly, none of those are in development yet, so any such mission would still be years away, if it happens at all.

But, based on what we're still continuing to learn from Cassini, the moon is only looking more and more intriguing.

"Even after its end," Glein said, "the Cassini spacecraft continues to teach us about the potential of Enceladus to advance the field of astrobiology in an ocean world."

The research has been published in the journal Nature.