Earthenware vessels can often be windows to the activities of long lost cultures. Traces of their contents can be clues to what we once snacked on, how we fed our children, and even how we cursed our enemies.

For decades, a number of conical vessels unearthed near Roman latrines were presumed to be recently emptied chamber pots. Evidence for this was purely circumstantial, yet what else would they be?

Now, archaeologists from the University of Cambridge in the UK and the University of British Columbia in Canada have confirmed these rather plain-looking containers were just what researchers thought.

Their analysis of mineralized concretions found inside earthenware dug up from the rural district of Gerace in central Sicily uncovered the preserved eggs of a species of intestinal worm.

"It was incredibly exciting to find the eggs of these parasitic worms 1,500 years after they'd been deposited," says University of Cambridge archaeologist Tianyi Wang.

Whipworms (Trichuris trichiura) have been a scourge on human bums for at least tens of thousands of years, having been picked up from similar parasites in African apes.

Today around 700 million or so individuals around the world carry the 4-centimeter-long (just under 2 inches) helminth in their bodies at any one time. The parasite makes its home in the large intestine, popping out egg after egg into our feces.

Usually they don't make their presence known, but with enough of them crowding out our guts they can become a serious health concern. Anemia, pain in the bowels, and even rectal prolapse can occur in some of the worst case scenarios.

It's not clear how big a problem whipworms might have been for the ancient Romans, but it's no surprise they had them. Studies on the remains of their latrines have showed their guts were crawling with all kinds of worm and amoeba that put them at risk of dysentery.

Yet this is the first time parasitic eggs have been observed in the residue of a ceramic vessel, confirming Romans did their business on the go.

"This pot came from the baths complex of a Roman villa," says Piers Mitchell, a parasite expert from the University of Cambridge.

"It seems likely that those visiting the baths would have used this chamber pot when they wanted to go to the toilet, as the baths lacked a built latrine of its own. Clearly, convenience was important to them."

The Roman site at the town of Gerace was uncovered in the 1990s, but most of what we know about the site has come from excavations carried out over the past decade. Researchers have since identified parts of a modest size villa with mosaics and marble decorations, sporting a bath house, store building, and even kilns, all dating to the 4th and 5th centuries CE.

We even know who owned the estate, with the words 'praedia Philippianorum' in the baths' cold room telling us it belonged to somebody called Philippiani.

Whether it was Philippiani's poop pot, or just used by his guests while they enjoyed his baths, we can only speculate. The vessel was uncovered high in the spoil of debris outside one of the baths' warm rooms, robbing it of important context.

Gerace villa, with location of chamber pot in red. (Rabinow et al., J. Archaeol. Sci., 2022)

Gerace villa, with location of chamber pot in red. (Rabinow et al., J. Archaeol. Sci., 2022)

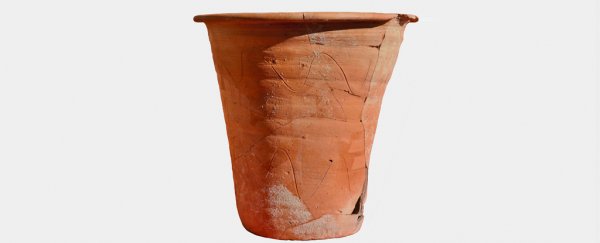

The container was typical of a type made in Sicily around that time, measuring precisely 31.8 centimeters (about 1 foot) with a diameter of 34 centimeters – a size appropriate for a squatting adult to sit over. More likely, a seat-less wicker or timber chair would have been used for added comfort.

As for decoration, a simple pair of parallel wavy lines was etched around its sides.

With this vessel confirmed as a chamber pot, other similar pots found around the empire are more likely to have once been used for the same purpose. Many are a little more ornate than this as well, or made from luxury materials.

Not all are sure to have been used for collecting bodily waste, though. A recent study on hundreds of vessels uncovered in the Serbian town of Viminacium suggested in addition to possible chamber pots, they could have stored cereals or water, or even been burial urns.

Did the ancient Romans reuse and recycle their food containers after they'd seen better days? Now that archaeologists know what to look for, it's possible they can go back to other vessels stored away in museums and archives, and scratch out some evidence.

"Where Roman pots in museums are noted to have these mineralized concretions inside the base, they can now be sampled using our technique to see if they were also used as chamber pots," says Mitchell.

This research was published in the Journal of Archaeological Science Reports.