New research shows cooking oil works fantastically well at repelling bacteria on some surfaces, potentially reducing levels by around 1,000 times on pots and pans – meaning kitchens and food processing sites that are much safer and more hygienic.

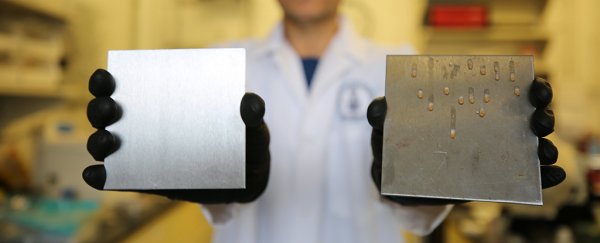

Mass production of food requires raw ingredients being handled in large stainless steel machines that are notoriously difficult to clean, with bacteria thriving in the small nicks and indentations that build up on these kind of surfaces over time.

But simply adding a thin layer of cooking oil on the metal surface can repel bacteria and prevent contamination from microorganisms like Salmonella, Listeria and E. coli, an international team of scientists has now shown. It's as simple as it sounds.

(Liz Do)

(Liz Do)

"Coating a stainless steel surface with an everyday cooking oil has proven remarkably effective in repelling bacteria," says one of the team, Ben Hatton from the University of Toronto in Canada.

"The oil fills in the cracks, creates a hydrophobic layer and acts as a barrier to contaminants on the surface."

These food-safe oil-based slippery coatings (FOSCs), to give them their official name, were developed based on previous research from Harvard. That earlier work looked at ways of trapping lubricants into materials to create a slippery but not sticky surface.

Adapting that research, experiments carried out by the team of scientists showed that drastic thousand-fold reduction on bacteria levels – the risk of cross-contamination and therefore foodborne illnesses drops significantly.

Further tests showed the coating could hold up to some pretty severe washing and still stay effective. It could also be reapplied fairly easily, the study shows, so machines could be kept bacteria-free over the long term.

While more work is going to be necessary before this can be implemented, it's potentially a simple, low-cost and safe way of preventing bacteria build-up in food preparation – and preventing bacteria build-up in the first place is a much more elegant solution than trying to remove it from microscopic cracks in a surface with abrasive chemicals.

The team of researchers is going to carry on looking at different combinations of oils and surfaces to see if they can improve on their already impressive results.

As the team points out, around 3,000 deaths a year are attributed to foodborne illnesses in the US, a figure that shoots up to 2 million a year in developing countries. A technique like this one, that can be introduced almost anywhere, can potentially save a lot of lives.

"Contamination in food preparation equipment can impact individual health, cause costly product recalls and can still result after chemical-based cleaning occurs," says Hatton.

The research has been published in ACS Applied Materials and Interfaces.