The line between human-made materials and living organisms just got more blurred. Researchers have created a new biomaterial that isn't alive, but which exhibits three key traits for life: metabolism, self-assembly, and organisation.

The new material can crawl forward like a slime mould, growing new strands from the front as the old ones at the back decay and fall away. The scientists have even set up races between competing material samples in the lab.

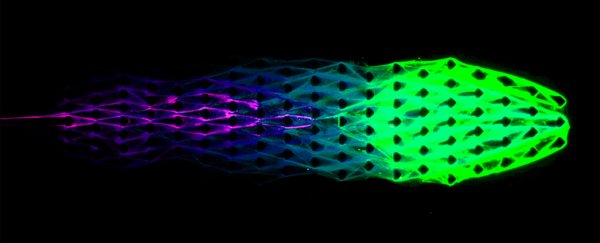

Underpinning it is a mechanism the scientists are calling DASH: DNA-based Assembly and Synthesis of Hierarchical materials. As with DNA in living organisms, the instructions for metabolism and regeneration are encoded in the biomaterial.

"We are introducing a brand new, life-like material concept powered by its very own artificial metabolism," says one of the team, Dan Luo from Cornell University in New York.

"We are not making something that's alive, but we are creating materials that are much more life-like than have ever been seen before."

At the core of DASH are nanoscale building blocks that can rearrange materials into polymers and eventually larger shapes, all from chains of repeating DNA just a few millimetres or hundredths of an inch long.

The material is grown from a 55-nucleotide base seed sequence, which when combined with a reaction solution, provides a liquid flow of energy to enable the DNA to synthesise new strands of its own.

"Everything from its ability to move and compete, all those processes are self-contained," says Luo. "There's no external interference. Life began billions of years from perhaps just a few kinds of molecules. This might be the same."

This life-imitating biomaterial is still very basic, but it sets the foundation for one day being able to develop robots that are able to construct themselves, without much human involvement at all. They could even be self-replicating one day, the researchers say.

We've seen in the past how biomaterials can be useful for augmenting machinery and robotics and even repairing the human body – this looks like being another important step forward for the field.

Further down the line the engineers are hoping that the material might be able to be programmed to avoid or be attracted to stimuli like food and light. Greater longevity for the material is in the pipeline too, as the researchers develop DASH.

"The designs are still primitive, but they showed a new route to create dynamic machines from biomolecules," says one of the researchers, Shogo Hamada from Cornell University. "We are at a first step of building life-like robots by artificial metabolism."

"Even from a simple design, we were able to create sophisticated behaviors like racing. Artificial metabolism could open a new frontier in robotics."

The research has been published in Science Robotics.